Intro

I really like to follow up stories about cybercrime and whatnot - related to cybersecurity. A person I am looking up to a lot when it comes to Opsec is Sam Bent (DoingFedTime), who was covering at the time the story of IntelBroker, a big name in the scene.

Long story short, this person got arrested and it got my curiousity as of how law enforcement managed to track him down. The main reason I read in the articles was related to crypto Opsec, to which (at the time) I was clueless. I started reading about crypto operational security and how can someone be tracked and after collecting and reading many articles, both related and unrelated to the story, I thought of making a post about it - more to act as personal notes for the future. To make sure of their correctness, I asked an llm to help me write this post (if it wasn’t noticable from the very start of it:P).

I hope you learn something as well. Personally the story and the world of crypto got me really fascinated.

The $250 mistake

In February 2025, French authorities arrested Kai West, a 25-year-old British national alleged to be the prolific cybercriminal known as “IntelBroker”1. West stands accused of orchestrating a series of high-profile data breaches targeting over 40 organizations, causing damages estimated to exceed $25 million worldwide2. For years, IntelBroker operated with a sophisticated understanding of digital security, allegedly administering the notorious cybercrime marketplace BreachForums and typically insisting on payments in Monero, a cryptocurrency renowned for its privacy features1. Yet, his downfall was not the result of a complex cryptographic failure or a brute-force attack on his infrastructure. It was precipitated by a single, seemingly minor deviation from his own security protocol: accepting a $250 payment in Bitcoin from an undercover FBI agent.1

This single transaction served as the digital fingerprint that allowed investigators to unravel his entire anonymous persona. The case of IntelBroker is not an anomaly but a stark and practical illustration of a fundamental principle in digital finance: the architectural philosophy of a cryptocurrency dictates its operational security posture. This report will argue that the core design choices of Bitcoin (prioritizing transparency for public verification) and Monero (mandating opacity for user privacy) create two vastly different ecosystems with profound and divergent implications for traceability. The IntelBroker investigation serves as a textbook example of how these architectural differences manifest under the pressure of a real-world forensic investigation, demonstrating that for any operation requiring financial confidentiality, the choice of instrument is a decisive and unforgiving factor.

The primary vulnerability that led to West’s capture was not a flaw in the technology he used, but a failure in human discipline. Law enforcement did not need to “break” the robust privacy of Monero; they successfully employed social engineering to persuade an operator to abandon his established security procedures and use a transparent system1. This underscores a critical lesson: operational security (OpSec) is a holistic discipline that encompasses human behavior, procedural consistency, and technological choices. The most secure cryptographic system is rendered ineffective if its user can be convinced to circumvent it.

To fully dissect this dynamic, this report will provide a comprehensive analysis structured as follows. First, it will deconstruct the nature of Bitcoin’s public ledger and its model of pseudonymity. Second, it will offer a detailed examination of Monero’s architecture, which is purpose-built for privacy by default. Third, it will provide a deep technical breakdown of the three cryptographic pillars that underpin Monero’s anonymity: Ring Signatures, Stealth Addresses, and Ring Confidential Transactions (RingCT). Fourth, it will conduct a forensic walkthrough of the IntelBroker case, detailing precisely how Bitcoin’s transparency was leveraged by investigators. Finally, it will conclude with an analysis of the strategic implications of these findings for law enforcement, privacy advocates, and any user of digital currencies.

Section 1: The Transparent Ledger - Deconstructing Bitcoin’s Pseudonymity

To comprehend why IntelBroker’s use of Bitcoin was a fatal error, one must first understand the fundamental architecture of the Bitcoin network. Its design, while revolutionary in enabling a decentralized financial system, was not optimized for privacy. Instead, it was built on a principle of radical transparency to achieve trustless consensus.

1.1 Pseudonymity, Not Anonymity

A common misconception is that Bitcoin is an anonymous currency. In reality, it is pseudonymous5. Transactions are not linked to real-world names or identities directly. Instead, they are associated with “addresses,” which are strings of alphanumeric characters. Anyone can generate any number of addresses without providing personal information, creating a layer of pseudonymity5.

However, every single transaction ever conducted on the Bitcoin network is recorded on a public, distributed ledger known as the blockchain6. This ledger is permanent and immutable. While the addresses themselves are pseudonymous, the flow of funds between them is completely transparent and available for anyone to inspect5. This public nature was a deliberate design choice, essential for allowing all participants in the network to independently verify transactions and agree on the state of the ledger without needing a central intermediary like a bank.

1.2 The Blockchain as a Public Bookkeeper

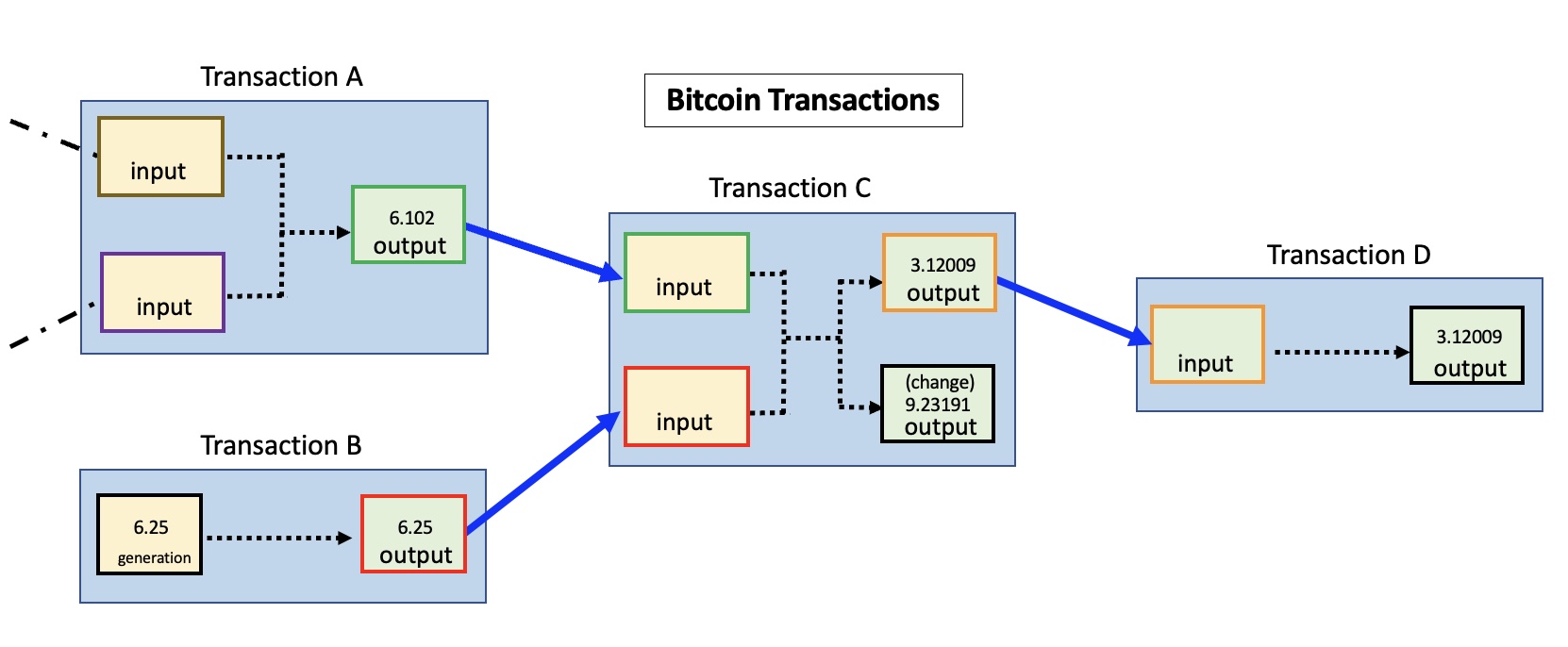

The Bitcoin blockchain functions like a global, public bookkeeping ledger. For every transaction, it permanently records three key pieces of information: the sending address(es), the receiving address(es), and the amount of Bitcoin transferred5. Imagine a bank that publishes every single transfer, showing the account numbers of the sender and receiver and the exact amount, but without listing the account holders’ names. In a simplified graph:

While individual transactions might seem disconnected, a dedicated observer can analyze this public data to identify patterns, link addresses together, and build a detailed graph of financial activity.

This inherent transparency has given rise to an entire industry of blockchain analytics firms. These companies use sophisticated software to trace the flow of funds across the network, cluster addresses that are likely controlled by the same entity, and monitor activity associated with illicit services like darknet markets or ransomware operations8.

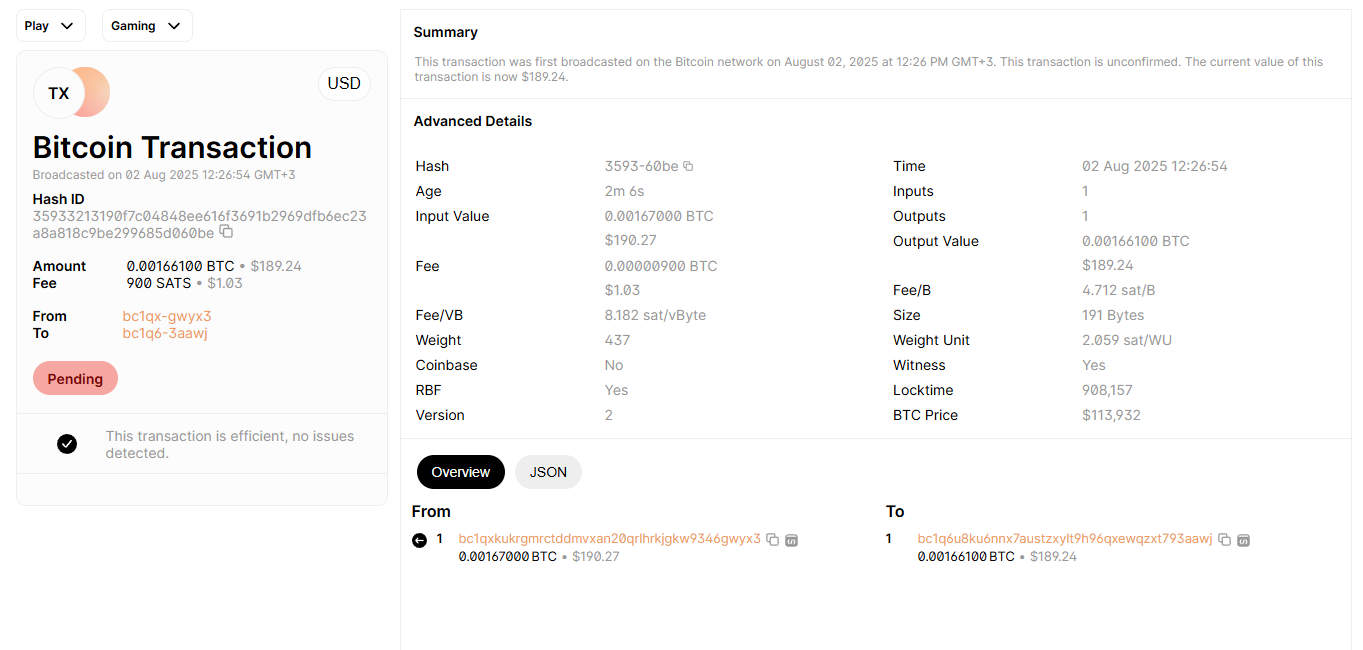

We can view real time transactions via websites such as the blockchain:

1.3 The Point of Failure: Linking Pseudonym to Person

The entire privacy model of Bitcoin rests on a single, fragile assumption: that a user’s pseudonymous address can never be linked to their real-world identity. Once this link is established, the veil of pseudonymity is permanently shattered5. Because the entire transaction history of that address is public and immutable, an investigator can retroactively analyze all past and future activity associated with it. This deanonymization is not temporary; it is a permanent unmasking of that address’s financial life7.

This characteristic makes the Bitcoin blockchain a latent forensic tool of unprecedented power. Unlike traditional financial records, which may be fragmented across multiple institutions with varying data retention policies, the blockchain is a single, global, and eternal database of evidence9. Law enforcement does not need to trace transactions in real time. They can afford to wait months or even years for a suspect to make a single mistake that links an address to their identity. Once that “key” is found, it unlocks a complete and unalterable history of financial activity, allowing investigators to map out a suspect’s entire network with a precision that is often impossible in the conventional banking system.

1.4 The Role of “Off-Ramps” and KYC

The most common way this identity link is forged is through interaction with the regulated financial system. To be practically useful for most people, cryptocurrency often needs to be converted into traditional fiat currency (like USD or EUR). The points where this conversion happens are known as “on-ramps” (fiat to crypto) and “off-ramps” (crypto to fiat)8. Major cryptocurrency exchanges, such as Coinbase or Ramp (the two used in the IntelBroker case), are financial institutions subject to strict regulations. These include Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Know-Your-Customer (KYC) laws, which legally require them to collect and verify the real-world identity of their users—typically through government-issued IDs and proof of address4. When a user sends Bitcoin to or from an account on one of these exchanges, they create a direct, legally documented, and undeniable link between their personal identity and their pseudonymous blockchain addresses. It is this very mechanism that law enforcement exploits to bridge the gap between the digital pseudonym and the physical person, as was demonstrated with devastating effect in the IntelBroker investigation4.

Section 2: The Opaque Protocol - Monero’s Architecture of Anonymity

In stark contrast to Bitcoin’s philosophy of transparency, Monero was designed from the ground up with a single, overriding objective: privacy. It is not based on Bitcoin’s code but on the CryptoNote protocol, a different technological foundation explicitly created to enable private, censorship-resistant, and untraceable digital cash12.

2.1 A Different Philosophy: Privacy by Default

The most significant distinction between Bitcoin and Monero lies in their default settings. On the Bitcoin network, privacy is an opt-in, user-managed effort that requires immense discipline and technical skill to maintain. On the Monero network, privacy is mandatory and enforced at the protocol level for every user and every transaction12. There is no way to accidentally send a transparent transaction on the Monero network; the obfuscation of transaction details is a non-negotiable feature of the system13. This “privacy by default” approach is central to its design and ensures that the security of the network’s users does not depend on their individual expertise or diligence.

2.2 The Three Pillars of Privacy

To achieve this comprehensive privacy, Monero employs a suite of three distinct but interconnected cryptographic technologies. Together, they form a triad that obscures the three critical components of any financial transaction: the sender, the receiver, and the amount5.

- Ring Signatures: This technology conceals the identity of the sender.

- Stealth Addresses: This technology conceals the identity of the receiver.

- Ring Confidential Transactions (RingCT): This technology conceals the amount being transferred.

By mandating the use of all three for every transaction, the Monero protocol ensures that an outside observer examining its blockchain cannot determine who sent money, who received it, or how much was exchanged13.

2.3 The Security Implications of Fungibility

This mandatory privacy has a crucial second-order effect: it makes Monero a truly fungible currency12. Fungibility is the property of a good or asset whose individual units are essentially interchangeable. For example, one U.S. dollar is identical to and exchangeable for any other U.S. dollar. Its value is not dependent on its history.

Bitcoin, due to its transparent ledger, is not perfectly fungible. A Bitcoin’s entire transaction history is public, which means a coin can become “tainted” if it was previously involved in illicit activity, such as a darknet market transaction or a ransomware payment14. Blockchain analysis firms can flag these tainted coins, and regulated exchanges or merchants may refuse to accept them, effectively creating a two-tiered system of “clean” and “dirty” Bitcoins. An innocent user could receive tainted coins without their knowledge and later find their assets frozen or their transactions censored16.

Monero’s architecture makes this form of analysis and censorship impossible. Since the history of every Monero coin (XMR) is completely obscured, no coin can be singled out or blacklisted based on its past. Every XMR is identical to every other XMR, just like physical cash14. This fungibility is not merely an economic property; it is a core security feature. It protects users from the downstream consequences of a coin’s unknown history and ensures that Monero remains a neutral and censorship-resistant medium of exchange, which is a foundational goal of the project16.

Section 3: Inside the Black Box: A Technical Analysis of Monero’s Privacy Technologies

Monero’s privacy is not a simple feature but the result of a sophisticated interplay of advanced cryptographic techniques. Understanding how these mechanisms work is essential to appreciating the profound difference in its security model compared to Bitcoin’s. This section provides a technical breakdown of Monero’s three pillars of privacy.

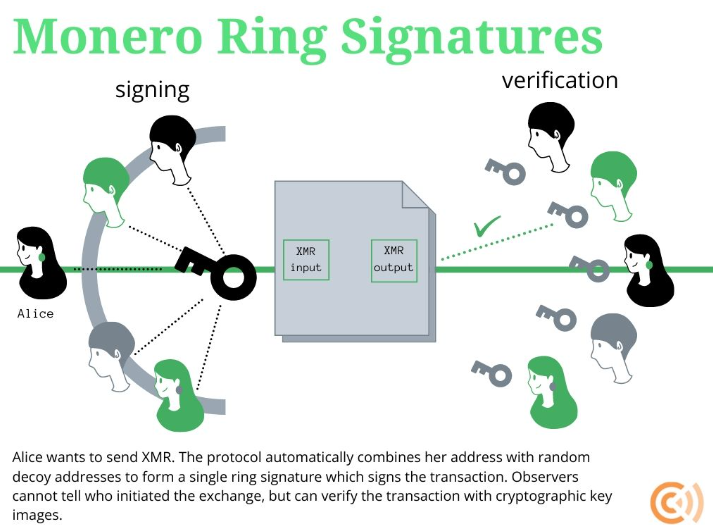

3.1 Sender Anonymity: Ring Signatures

The first pillar, which protects the sender’s identity, is the ring signature. A ring signature is a type of cryptographic digital signature that can be produced by any member of a group (a “ring”) of potential signers, each with their own private key. The resulting signature mathematically proves that the transaction was signed by one of the members of the ring, but it is computationally infeasible for an outside observer to determine which member was the actual signer18. This provides the sender with plausible deniability.

In Monero’s implementation, when a user initiates a transaction, their wallet software automatically selects a number of other transaction outputs from the blockchain to act as “decoys” or “mixins”14. These decoys are combined with the user’s actual output (the funds they are spending) to form the ring. The current ring size in Monero is 16, meaning every transaction includes the true sender plus 15 decoys21. The signature generated applies to the entire ring, making it appear to an observer that any of the 16 participants could have been the true sender18. This process is spontaneous and non-custodial; the sender does not need to coordinate with or trust the owners of the decoy outputs22.

To prevent a user from spending the same funds twice (a “double-spend” attack), Monero employs a mechanism called a key image. A unique key image is mathematically derived from the actual output being spent, using the sender’s private key. The formula for a key image (I) is I=xHp(P), where x is the user’s private key and Hp(P) is a hash of their public key P21. This key image is published with every transaction. The Monero network maintains a list of all used key images and will reject any new transaction that attempts to submit a key image that has already been used. Because the derivation is a one-way function, the key image cannot be used to reveal the actual public key it corresponds to within the ring, thus preserving the sender’s anonymity while guaranteeing the integrity of the ledger24.

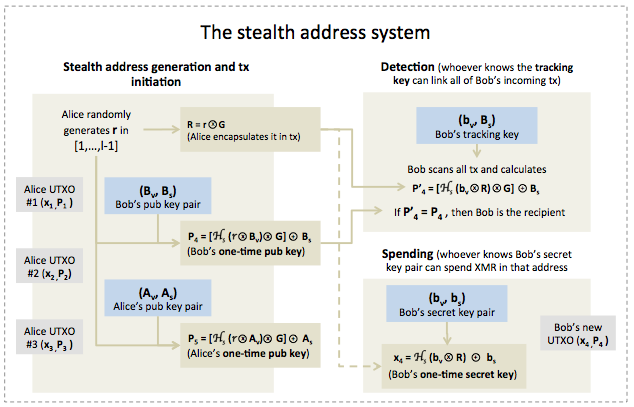

3.2 Recipient Anonymity: Stealth Addresses

The second pillar protects the privacy of the recipient using a technology known as stealth addresses. This mechanism ensures that the recipient’s public address is never recorded on the blockchain, preventing anyone from linking multiple payments to the same person26.

A Monero user has a single public address that they can share to receive funds. However, when someone sends them XMR, the sender’s wallet uses the recipient’s public address to automatically generate a unique, random, one-time destination address for that specific transaction5. The funds are sent to this one-time address, which appears on the blockchain.

More info here

This process is enabled by Monero’s dual-key structure. Each Monero account has two pairs of keys:

- Spend Keys (private and public): The private spend key authorizes the spending of funds from the account.

- View Keys (private and public): The private view key allows the user to see incoming transactions sent to their account.

The sender uses the recipient’s public view key and public spend key to generate the one-time stealth address. The recipient, in turn, uses their private view key to continuously scan the blockchain for any transactions destined for them. Their wallet software can recognize which of the millions of transactions belong to them and can then use their private spend key to access and spend those funds16. To an outside observer, every transaction on the Monero blockchain appears to go to a new, unique address that has never been used before and will never be used again, making it impossible to identify the actual recipient or link different payments together29.

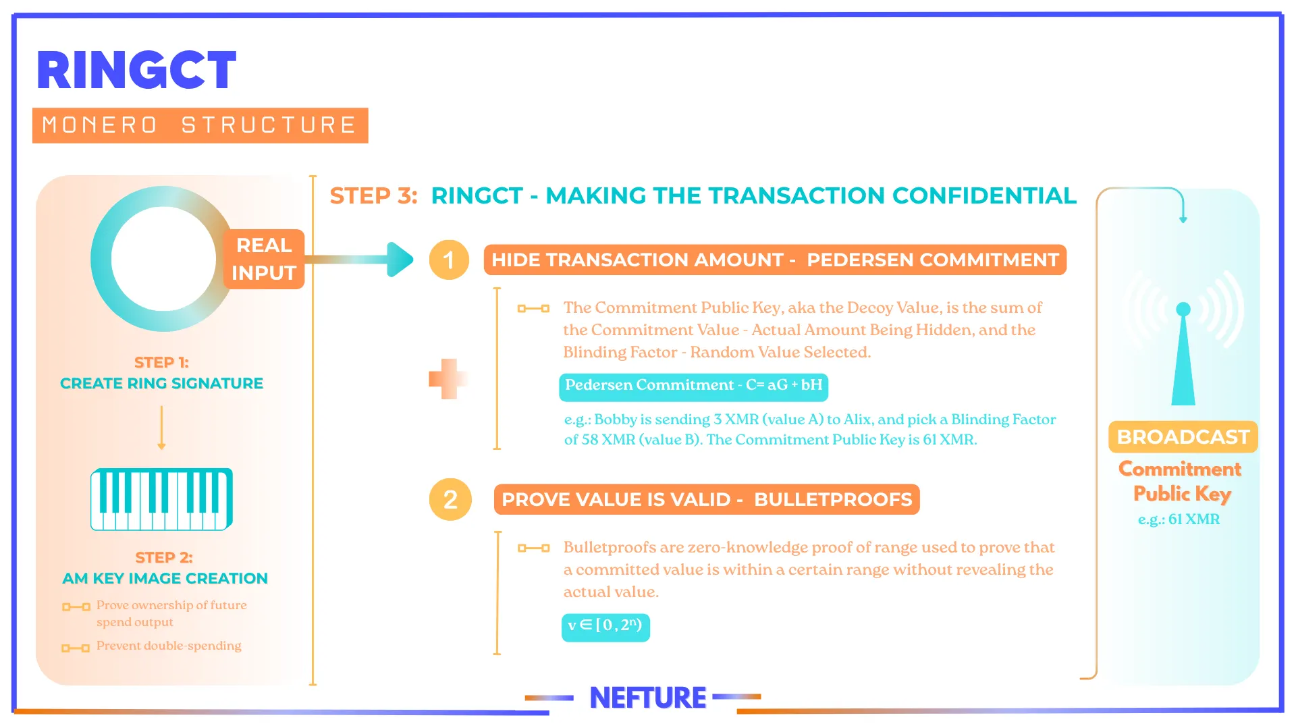

3.3 Amount Anonymity: Ring Confidential Transactions (RingCT)

The third and final pillar, which became mandatory in 2017, is Ring Confidential Transactions (RingCT). This technology hides the amount of XMR being transferred in every transaction14. RingCT uses a cryptographic commitment scheme known as a Pedersen Commitment. Instead of recording the actual transaction amount on the blockchain, the sender publishes an encrypted “commitment” to the amount. A Pedersen Commitment has a unique mathematical property: commitments can be added and subtracted while they are still encrypted. This allows the Monero network to verify the validity of a transaction without knowing the actual values22. Specifically, the protocol verifies that the sum of the input commitments equals the sum of the output commitments ($ \sum C_{in} = \sum C_{out} $). If the equation balances, the network can confirm that no XMR was created or destroyed, thus maintaining the integrity of the money supply without revealing the transaction amount16.

A critical component of this system is the range proof. The Pedersen Commitment scheme alone is not sufficient, as a malicious user could create money by using negative numbers (e.g., sending 2 XMR to receive an output of 5 XMR and a change output of -3 XMR; the equation would still balance). To prevent this, senders must also include a range proof, which cryptographically proves that the value of each committed output is a positive number within a certain range (specifically, greater than zero)31. Monero uses a highly efficient and compact form of range proof called Bulletproofs, which significantly reduces the size and cost of transactions compared to earlier implementations34.

The combination of these three mandatory technologies creates a multi-layered defense that makes Monero’s blockchain fundamentally opaque.

| Feature | Bitcoin (BTC) | Monero (XMR) |

|---|---|---|

| Sender Identity | Pseudonymous (Public address visible) | Anonymous (Hidden within a ring of 16 signers via Ring Signatures) |

| Recipient Identity | Pseudonymous (Public address visible) | Anonymous (Hidden via one-time Stealth Addresses) |

| Transaction Amount | Public (Visible on the blockchain) | Confidential (Hidden via Ring Confidential Transactions) |

| Ledger Visibility | Transparent (All transaction details are public) | Opaque (Sender, receiver, and amount are all obscured) |

| Fungibility | Non-Fungible (Coins can be “tainted” by history) | Fungible (All coins are identical and interchangeable) |

| Privacy Basis | Optional (User-managed, requires discipline) | Mandatory (Enforced by the protocol for all transactions) |

Section 4: Case Study - The Digital Fingerprint That Caught ‘IntelBroker’

The theoretical differences between Bitcoin and Monero were put to a definitive, high-stakes test in the investigation that led to the arrest of Kai West. The case serves as a practical, step-by-step demonstration of how the transparency of the Bitcoin ledger can be leveraged by law enforcement to methodically dismantle a sophisticated cybercriminal’s anonymity.

4.1 The Sting: Exploiting the Human Element

Kai West, operating as IntelBroker, was a prominent figure in the cybercrime underground. He was an alleged administrator of BreachForums, a successor to the infamous RaidForums, which served as a major marketplace for stolen data1. His posts on the forum, offering data stolen from major corporations and government agencies, explicitly stated that he accepted payment via Monero, indicating a clear awareness of the need for financial privacy in his operations3. The breakthrough for investigators came not from cracking Monero’s cryptography, but from exploiting human fallibility. In January 2023, an undercover FBI agent, posing as a potential buyer for stolen data, engaged with IntelBroker4. During their interaction, the agent successfully persuaded West to make a critical exception to his own operational security rules. Instead of demanding Monero as usual, West agreed to accept a payment of $250 in Bitcoin1. This decision, likely driven by convenience or confidence, was the single point of failure that compromised his entire operation. By accepting the Bitcoin, he created a permanent, public, and traceable link on an open ledger—a digital fingerprint.

4.2 Following the Money: A Play-by-Play of the Bitcoin Trace

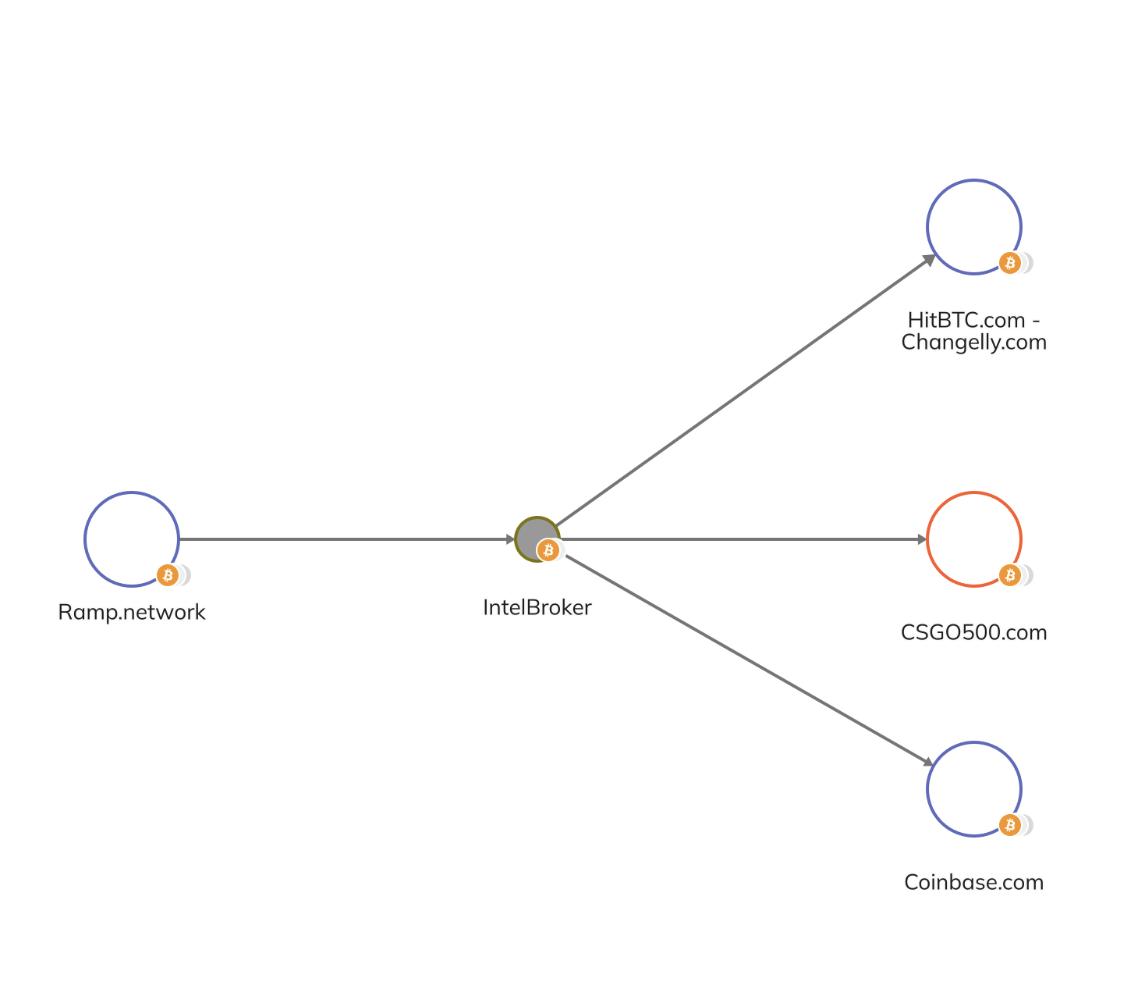

The undercover agent sent the Bitcoin payment to the address West provided: bc1qj52d3d4p6d9d72jls6w0zyqrrt0gye69jrctvq4. This transaction was the starting point for the forensic analysis. Using specialized blockchain intelligence software, specifically Chainalysis Reactor, investigators began to “follow the money”4.

The analysis of this single address revealed West’s broader financial infrastructure. The public nature of the Bitcoin ledger allowed investigators to trace the flow of funds both into and out of this address, connecting it to other services and accounts. The trace revealed direct interactions with two key choke points: the regulated cryptocurrency exchanges Ramp and Coinbase4. This is a classic example of law enforcement’s strategy of tracing illicit funds to the “off-ramps” where they connect with the traditional, regulated financial system. The analysis also uncovered other on-chain activities linked to the persona, including small deposits to the online cryptocurrency casino CSGO500 and transactions involving an Ethereum address that IntelBroker had publicly advertised4. This comprehensive mapping of his financial activity was only possible because every transaction was recorded on a public ledger.

| Date | Event | Investigative Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Jan 2023 | Undercover FBI agent contacts IntelBroker to purchase stolen data.⁴ | Establishes a direct line of communication with the target. |

| Jan 2023 | Agent convinces IntelBroker to accept a $250 payment in Bitcoin, a deviation from Monero.¹ | The critical OpSec failure. A traceable link is created on a public ledger. |

| Post-Transaction | Investigators use Chainalysis Reactor to analyze the Bitcoin address bc1qj52d3d4p6d9d72jls6w0zyqrrt0gye69jrctvq.⁴ | The forensic investigation begins, leveraging the transparency of the Bitcoin blockchain. |

| Analysis Period | The trace reveals interaction with accounts at regulated exchanges Ramp and Coinbase.⁴ | Identifies the critical “off-ramp” choke points where the digital persona connects to the regulated world. |

| Analysis Period | Law enforcement obtains account information from Ramp and Coinbase through legal process.⁴ | The KYC/AML regulations force exchanges to collect and provide real-world identity data. |

| Data Review | Ramp data links the account to ‘Kai Logan West’. Coinbase links alias ‘Kyle Northern’ to ‘Kai West’.⁴ | The “smoking gun.” The pseudonymous blockchain activity is irrefutably linked to a real-world identity. |

| Feb 2025 | Kai West is arrested by French authorities.¹ | The culmination of the investigation, made possible by the initial Bitcoin trace. |

| Jun 2025 | DOJ unseals indictment charging Kai West with conspiracy, wire fraud, and computer intrusions.² | Formalizes the charges based on the evidence gathered, with the Bitcoin transaction as a key piece. |

4.3 The Choke Point: From Pseudonym to Person

The final and most decisive step in the investigation was leveraging the identified links to regulated exchanges. Having established that the Bitcoin address in question was connected to accounts at Ramp and Coinbase, law enforcement agencies had the legal grounds to compel these companies to provide the associated user information4. The Know-Your-Customer (KYC) data held by these exchanges provided the irrefutable evidence needed to bridge the gap between the online persona and the physical individual. The records from Ramp directly associated the cryptocurrency activity with the name ‘Kai Logan West’ and his date of birth. The records from Coinbase, while opened under the alias ‘Kyle Northern,’ contained underlying KYC documentation that ultimately linked back to ‘Kai West’4. This information, combined with other corroborating evidence like IP address overlaps, allowed authorities to definitively identify IntelBroker as Kai West, leading to his arrest in France and subsequent indictment in the Southern District of New York1. The entire investigative chain, from the initial sting to the final arrest, was anchored by the unchangeable and public record of a single Bitcoin transaction.

Section 5: Analysis and Strategic Implications

The IntelBroker case is more than the story of a single cybercriminal’s capture; it is a landmark event that clarifies the strategic landscape of financial privacy and surveillance in the digital age. Its outcome has significant implications for law enforcement, privacy advocates, and technology developers, highlighting a clear asymmetry of effort in tracing different cryptocurrencies and fueling an ongoing technological arms race.

5.1 The Asymmetry of Effort

The investigation demonstrates a vast disparity in the resources, expertise, and probability of success required to trace Bitcoin versus Monero. Tracing funds on the Bitcoin network has become a standardized, almost routine practice for well-equipped law enforcement and intelligence agencies8. An entire ecosystem of analytics firms provides powerful tools that automate much of this process, making it accessible to a growing number of investigators7. In contrast, reliably tracing Monero transactions remains a “grand challenge” in the field of digital forensics. The multi-layered privacy protections of Ring Signatures, Stealth Addresses, and RingCT are not susceptible to the same kind of straightforward graph analysis that works on Bitcoin. The difficulty is so significant that government agencies like the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) have offered public bounties of hundreds of thousands of dollars to any entity that can develop reliable methods for cracking Monero’s anonymity36. While some academic research and leaked presentations from analytics firms suggest potential theoretical weaknesses or heuristic attacks, particularly if a single entity controls a large portion of network activity, these methods are far from being routinely applicable or forensically sound37. Breaking Monero’s privacy requires an extraordinary level of effort and resources, whereas tracing Bitcoin requires only a single mistake from the target. This case effectively provides a blueprint for law enforcement agencies worldwide. It demonstrates that the most efficient strategy for tackling privacy coins is not to engage in a costly and likely futile cryptographic battle. Instead, the playbook is to use social engineering, informant operations, or other investigative techniques to manipulate the target into moving their funds onto a transparent ledger like Bitcoin’s. Once the activity is on a public blockchain, the focus can shift to the well-established and highly effective strategy of monitoring regulated on/off-ramps for the inevitable KYC link. For privacy seekers and illicit actors, the warning is equally stark: a single moment of lax discipline or a single deviation from a secure protocol can be enough to permanently unravel years of careful operational security

5.2 The Ongoing Arms Race

The world of cryptocurrency privacy is not static; it is a dynamic arms race between those building privacy tools and those seeking to circumvent them. The IntelBroker case is a single snapshot in this continuous conflict. As law enforcement and analytics firms refine their tracing methodologies and expand their data collection from exchanges and other sources9, privacy-oriented projects are simultaneously working to patch vulnerabilities and strengthen their defenses. Monero, for instance, has a history of proactive development, implementing regular, scheduled network upgrades (hard forks) to introduce improved cryptographic schemes. The mandatory implementation of RingCT in 2017, the later introduction of more efficient Bulletproofs range proofs, and the adoption of the CLSAG ring signature scheme are all examples of this evolutionary process13. These upgrades are designed to close potential loopholes, increase the size of the anonymity set, and make transactions more efficient and secure. The battle for financial privacy is being fought in the code itself, with each side adapting to the other’s latest innovations.

5.3 The Inevitable Contradiction: Usability vs. Privacy

The case also highlights a fundamental tension at the heart of cryptocurrency: the trade-off between real-world usability and maximum privacy. For a digital currency to be useful to the average person, it must be easily convertible to and from the fiat currencies used for everyday life. This necessitates interaction with the regulated financial system—the exchanges, brokers, and payment processors that serve as on- and off-ramps8. However, as the IntelBroker case proves, these regulated points of interaction are the primary vector for deanonymization. They are the choke points where privacy-seeking individuals are forced to reveal their real-world identities. This creates an inherent contradiction. To achieve the highest level of financial privacy, a user would ideally need to remain within a closed-loop, crypto-only ecosystem, using decentralized exchanges or peer-to-peer methods that do not require KYC. Yet, this approach significantly limits the currency’s utility for paying rent, buying groceries, or participating in the broader economy. It also introduces its own set of risks and complexities, requiring a high degree of technical sophistication and consistent operational security. True financial privacy, therefore, is not a simple switch one can flip; it demands a rigorous and unwavering commitment to security protocols, especially at the vulnerable boundaries where the digital world meets the traditional one.

Section 6: Advanced Evasion Techniques, Laundering, and the Fungibility Problem

Beyond the foundational differences between Bitcoin and Monero, illicit actors employ a range of advanced techniques to launder funds and evade detection. However, these methods often contain their own operational security risks. Understanding these techniques, along with the critical concept of fungibility, provides a more complete picture of the cryptocurrency privacy landscape.

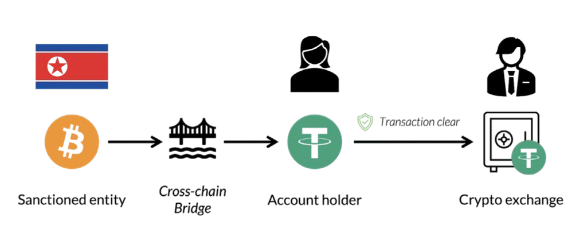

6.1 The Chain-Hop Fallacy: Tracing Cross-Chain Swaps

A common technique used to obscure the flow of funds is “chain hopping,” where a user swaps a cryptocurrency from one blockchain to another, often multiple times39. For example, a user might swap illicitly obtained Bitcoin for Monero, and then later swap that Monero back into Bitcoin or another cryptocurrency. This is often done through cross-chain bridges or “instant swap” services that may not require stringent KYC checks38. The goal is to complicate the money trail, forcing investigators to engage in hours of manual tracing to connect the transactions across different ledgers40.

However, this method is not a panacea for anonymity. While the transaction within the Monero network is opaque, the entry and exit points are not. The initial transaction swapping Bitcoin for Monero is visible on the public Bitcoin blockchain, as is the final transaction where Monero is swapped back to Bitcoin41. Investigators can analyze these public transactions. If the amount, timing, and other metadata of the outgoing Bitcoin transaction correlate with the incoming transaction on the other side of the swap, it can create a strong link, effectively bridging the privacy gap created by Monero42. This risk is amplified when using centralized or semi-centralized swap services, which may keep logs or have identifiable transaction patterns that can be analyzed by law enforcement38.

6.2 A Survey of Cryptocurrency Laundering Techniques

Money laundering in cryptocurrency follows the same three basic stages as in traditional finance: placement (introducing illicit funds into the system), layering (obscuring the source through complex transactions), and integration (reintroducing the funds into the legitimate economy)43. Bitcoin Laundering Techniques: Because Bitcoin’s ledger is transparent, criminals must employ active layering techniques to hide their tracks. Common methods include:

- Mixers and Tumblers: These services pool and mix funds from many different users to break the traceable chain of ownership45. A user sends Bitcoin to a mixer and receives different bitcoins back (minus a fee), making it difficult to connect the input to the output48. However, these services are a major target for law enforcement. Centralized mixers can have their logs seized, and several, like ChipMixer and the operators of Samourai Wallet, have faced legal action39.

- Chain Hopping: As described above, rapidly swapping funds across different blockchains is a primary laundering technique39.

- Intermediary Hops: Criminals create complexity by sending funds through a long series of intermediary wallets they control before moving them to an off-ramp50.

- High-Risk Services: Using services known for lax compliance, such as certain unregulated exchanges or online gambling platforms, to cash out or further obscure funds44.

Monero as a Laundering Technique: With Monero, the laundering process is fundamentally different. The currency’s protocol itself provides the “layering” stage automatically. The primary technique is simply to convert illicit funds (like Bitcoin from a ransomware attack) into Monero43. Once the funds are on the Monero blockchain, its mandatory privacy features—Ring Signatures, Stealth Addresses, and RingCT—make the transaction trail untraceable12. The funds are effectively laundered the moment they are converted to XMR. From there, the “clean” funds can be swapped back to a more liquid currency like Bitcoin or a stablecoin and sent to a regulated exchange for integration into the fiat system, with the link to the original crime having been severed by Monero’s opaque ledger41. This inherent laundering capability is why Monero has become the currency of choice for many darknet markets and cybercriminal operations38.

6.3 The Fungibility Graveyard: Understanding ‘Tainted’ Bitcoin

The concept of “tainted” coins is a direct consequence of Bitcoin’s transparent ledger and is central to understanding its privacy limitations.

- What is Fungibility? Fungibility is an essential property of money, meaning that each unit of a currency is interchangeable with any other unit53. One dollar is as good as any other dollar, regardless of its history.

- Bitcoin’s Taint Problem: Because every Bitcoin transaction is public, individual coins have a permanent, traceable history55. Blockchain analysis firms can analyze this history and apply a “taint” label to coins that have been associated with illicit activities like hacks, scams, or darknet markets55. Taint is a probabilistic score indicating a coin’s proximity to crime57.

- The Fungibility Graveyard: This term describes the consequence of taint. A “tainted” Bitcoin is no longer perfectly interchangeable with a “clean” one. Regulated exchanges and merchants may refuse to accept tainted coins, freeze accounts that receive them, or report the user to authorities to comply with anti-money laundering laws55. This creates a two-tiered system where a coin’s history dictates its present-day value and usability. An innocent person could accept a payment in Bitcoin, only to find later that the coins are considered “tainted” and cannot be spent or deposited, effectively sending them to a “fungibility graveyard”53.

- Monero’s Inherent Fungibility: In contrast, Monero is designed to be truly fungible, like physical cash43. Since no transaction’s history can be traced, no individual Monero coin can be identified or blacklisted as “tainted”12. This ensures that all units of Monero are equal and interchangeable, which is a critical security feature that protects users from censorship and the unknown history of the money they receive43.

Conclusion: The Dichotomy of Transparency and Privacy

The comparative analysis of Bitcoin and Monero, brought into sharp relief by the forensic investigation of ‘IntelBroker’, reveals that these are not merely two different cryptocurrencies but the expressions of two fundamentally opposed design philosophies. Bitcoin was engineered for auditable transparency, creating a trustless system by making every transaction a matter of public record. Monero was engineered for cash-like opacity, creating a private system by making every transaction’s details confidential by default. Neither architecture is inherently superior in a vacuum; their value and their risks are entirely context-dependent. The definitive lesson from the downfall of Kai West is a crucial one for operational security in the 21st century: on a public ledger like Bitcoin’s, privacy is a fragile and temporary state, entirely dependent on perfect, perpetual user discipline. It is a veil that can be irrevocably pierced by a single mistake. On an opaque ledger like Monero’s, privacy is the robust, default state of the system, and breaching it requires an attacker to overcome formidable cryptographic barriers. A single mistake on Bitcoin’s ledger is permanent and fatal to anonymity; a mistake when using Monero is far less likely to occur at the protocol level and far more difficult for an adversary to exploit. Ultimately, the choice between these systems comes down to an assessment of risk and intent. For individuals or organizations whose activities demand robust and resilient financial privacy, the choice of technology cannot be an afterthought or a matter of convenience. The IntelBroker case will be remembered as the classic, unforgiving example of this principle: when confidentiality is paramount, privacy must be an architectural guarantee of the financial instrument itself, not an optional feature left to the fallible discipline of its user.

References

- [1] Notorious Hacker 'IntelBroker' Arrested - Cyber Security Intelligence

- [2] Notorious cybercriminal 'IntelBroker' arrested in France, awaits extradition to US

- [3] Southern District of New York | Serial Hacker “IntelBroker” Charged

- [4] The IntelBroker Takedown: Following the Bitcoin Trail - Chainalysis

- [5] Blog - Bitcoin vs. Monero - Anycoin

- [6] Bitcoin vs Monero: A Comprehensive Comparison for Investors

- [7] Cryptocurrency tracing - Wikipedia

- [8] How Blockchain Analytics Aids LEA's in Tracing Crypto Assets to Off-Ramps

- [9] Law enforcement in the age of cryptocurrency - Police1

- [10] How blockchain data can be leveraged by law enforcement agencies - Merkle Science

- [11] British hacker 'IntelBroker' charged in US over spree of company breaches - The Record

- [12] What is Monero (XMR)? | Monero - secure, private, untraceable

- [13] FAQ | Monero - secure, private, untraceable

- [14] Monero: Privacy and security in the world of cryptocurrencies | Onrec

- [15] XMR explained: a comprehensive guide to Monero's privacy-focused token - OKX

- [16] What is Monero and How Does it Achieve Privacy? - Edge

- [17] edge.app

- [18] Ring Signature | Moneropedia | Monero

- [19] Ring signature - Wikipedia

- [20] What are Ring Signatures?

- [21] On Monero's Ring Signatures - Cronokirby

- [22] Ring Confidential Transactions - Monero

- [23] How exactly do ring signatures work? : r/Monero - Reddit

- [24] Introduction to Monero and how it's different - University of Hawaii Maui College

- [25] Brief Dive into Ring Signatures - DEV Community

- [26] Stealth Address | Moneropedia | Monero

- [27] Stealth Address (Cryptocurrency): Meaning and Concerns - Investopedia

- [28] What are stealth addresses, and how do they work? - Cointelegraph

- [29] What is Stealth Address technology and Why Does Monero Use It? - SerHack

- [30] Ring CT | Moneropedia | Monero

- [31] (PDF) Monero RingCT explained - ResearchGate

- [32] Monero: Ring Confidential Transactions - YouTube

- [33] Ring Confidential Transactions - Ledger

- [34] Monero vs Bitcoin (Monero explained) - YouTube

- [35] Bulletproofs | Moneropedia | Monero

- [36] Ring Signature Definition - CoinMarketCap

- [37] A Deep Dive on Monero Tracing And Key Image Analysis : r/CryptoCurrency

- [38] The Rise of Monero: Traceability, Challenges, and Research Review | TRM Blog

- [39] How do cybercriminals launder cryptocurrency? | Barracuda

- [40] New Elliptic Report: Cross-chain money laundering reaches $22 ...

- [41] The (near) impossibility of tracing Monero - CYJAX

- [42] Monero's Decentralized P2P Exchanges: Functionality, Adoption, and Privacy Risks - arXiv

- [43] Money Laundering Using Cryptocurrencies

- [44] Cryptocurrency Money Laundering Guide: Meaning, Risks & Prevention - HyperVerge

- [45] Cryptocurrency tumbler - Wikipedia

- [46] What is a Bitcoin mixer? - Coinbase

- [47] Mixers and Tumblers: Regulatory Overview and Use in Illicit Activities | Merkle Science

- [48] Bitcoin mixer - Bitcoin Wiki

- [49] 2024 Crypto Money Laundering Report - Chainalysis

- [50] Report: Money laundering and Cryptocurrency

- [51] How Illicit Actors Launder Money Through Crypto Exchanges - Sanctions.io

- [52] Cryptocurrencies For Criminals: The 5 Most Relevant ...

- [53] Fungibility - Bitcoin Wiki

- [54] Fungibility: What It Means and Why It Matters - Investopedia

- [55] Understanding Bitcoin Fungibility - River

- [56] What is Bitcoin Fungibility And Its Factors? - Nadcab Labs

- [57] river.com